The IIAR has just announced a Public Review of their IIAR 2 standard. IIAR 2 is the “Safety Standard for Design of Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems” so it’s worth reviewing.

September 11, 2020 To: IIAR Members Re: Second (2nd) Public Review of Standard BSR/IIAR 2-202x, Safety Standard for Design of Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems. A second (2nd) public review of draft standard BSR/IIAR 2-202x, Safety Standard for Design of Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems is now open. The International Institute of Ammonia Refrigeration (IIAR) invites you to make comments on the draft standard. Substantive changes resulting from this public review will also be provided for comment in a future public review if necessary. BSR/IIAR 2-202x specifies the minimum safety criteria for design of closed-circuit ammonia refrigeration systems. It presupposes that the persons who use the document have a working knowledge of the functionality of ammonia refrigerating system(s) and basic ammonia refrigerating practices and principles. This standard is intended for those who develop, define, implement and/or review the design of ammonia refrigeration systems. This standard shall apply only to closed-circuit refrigeration systems utilizing ammonia as the refrigerant. It is not intended to supplant existing safety codes (e.g., model mechanical or fire codes) where provisions in these may take precedence.

IIAR has designated the revised standard as BSR/IIAR 2-202x. Upon approval by the ANSI Board of Standards Review, the standard will receive a different name that reflects this approval date.

We invite you to participate in the second (2nd) public review of BSR/IIAR 2-202x. IIAR will use the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) procedures to develop evidence of consensus among affected parties. ANSI’s role in the revision process is to establish and enforce standards of openness, balance, due process and harmonization with other American and International Standards. IIAR is the ANSI-accredited standards developer for BSR/IIAR 2-202x, and is responsible for the technical content of the standard.

This site includes links to the following attachments:

The 45-day public review period will be from September 11, 2020 to October 26th, 2020. Comments are due no later than October 26th, 2020.

Thank you for your interest in the public review of BSR/IIAR 2-202x, Safety Standard for Design of Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems.

Make your voices heard and comment to the IIAR!

Below is a quick review of the significant suggested changes and my thoughts on them.

1.3.3) Now requires “alternative means and methods” to be approved by a designed that is a licenced engineering professional. – This was common practice and helps you build a defensible case.

2) Definitions. Added a definition of car-seal. I’m happy the IIAR has finally acknowledged this industry practice!

3.3) Moved a reference to IIAR 7 on SOPs to the Informative appendix. Not sure this matters much as IIAR 2 still refers to IIAR 6 which references IIAR 7.

5.5.3) Saturation Pressures and Minimum Design Pressure. – They seem to have fixed the weird situation where your calculated low-side pressure could be higher than your minimum high-side pressure.

5.8) Clarified that purging piping shall be compatible with NH3. This was requirement always in there, you just had to bounce around the standard to find it.

5.11.4) Seems to add a new explicit requirement to document “the basis for the support design including the anticipated loads, demonstration that the support design is adequate for the anticipated loads, and that the supports meet or exceed the equipment manufacturer’s recommendations”

5.12.4.2) Clarifies that accessibility to “isolation valves identified as being part of the system emergency shutdown procedure” must be provided for people in emergency response PPE.

5.14) Removed wind indicators as being required by IIAR 2

5.14.1) System signage requirements to reference “maximum intended inventory”, remove the quantity of oil requirement, and replace test pressures with design pressures. – That “maximum intended inventory” is going to cause a ton of confusion when the sign says the “maximum intended inventory” is 20,000lbs but the actual inventory documentation shows 17,500lbs.

5.14.3) Changes the requirement for Emergency Shutoff Valve Identification from “uniquely identified” (which you could meet with valve tags) to “uniquely identified as emergency shutoff valves” both on the valves themselves and on the system drawings. This is going to be a major change for most people. I don’t think this change is worth the trouble it will cause.

6.10.2) New requirement that “Machinery room doors shall open with the use of only the panic hardware and shall not require the use of other hardware or switches to exit the room.” which was a pet-peeve of mine.

6.12.1) Requires the E-stop to be “manually reset”

6.12.2) Removes the “protected from inadvertent operation” requirement for ventilation switches

6.13) Essentially this section strongly advocates for 2 NH3 detectors in the machinery room but does provide provisions for only 1.

6.13.2.3) Now requires audible alarms to be “manually reset by a switch located in the machinery room or alternatively in an area remote from the machinery room.” – This will be a significant control change for most people.

6.14.7.6) New language “A means of proving emergency airflow shall be provided. Failure to prove airflow when the emergency ventilation fans are energized shall provide notice to a monitored location. Devices that can be used to prove emergency airflow include, but are not limited to: 1) pressure differential switches 2) sail switches 3) current monitors. ” – This reflects what most people are doing anyway.

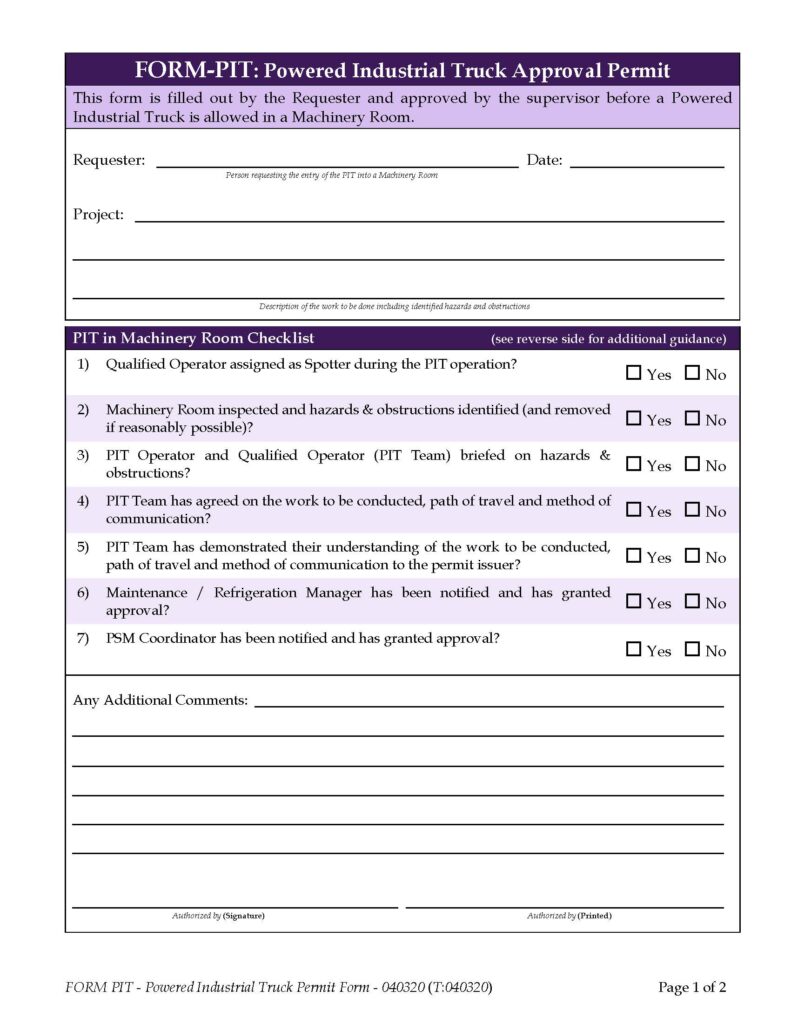

7.2.5) Stronger language: “Protection of Equipment from Physical Damage. Where ammonia equipment is installed in a location subject to physical damage from powered vehicles normally operating in the area, guarding or barricading shall be provided.”

15.1.2) Allows car-seals downstream of relief valves that relieve internal to the system. – This has been the practice for years, so it’s nice that the IIAR has finally acknowledged it.

15.2.5) Removes the exception “The vapor relief connection on an oil drain pot and similar applications shall be located at the highest point on the vessel.”

15.2.6) New requirement “Pressure relief devices intended for liquid pressure relief shall be connected below the anticipated liquid ammonia level and shall discharge internal to the system. “

15.2.9.1) New language “The employee of that device manufacturer or company holding a certification who last set and calibrated the pressure relief device shall seal the valve with a car seal.” – Calling it a car-seal is going to cause a ton of confusion here. This language should revert to the old language as just being sealed.

15.4.6) Stronger language added here “Liquids and other refrigerants shall not be vented into a common relief piping system used to convey ammonia vapor.”

15.5) They changed the formulas for relief discharge piping. According to our engineering department, it’s mostly semantics and not substantive.

15.6.4) I believe this new wording just states what was already required by other codes/standards “15.6.4 Liquid Overpressure Protection required. Relief valves used for liquid pressure protection of vessels and equipment constructed in accordance with the ASME B&PV code are required to be constructed and marked in accordance with the ASME B&PV Code.”

15.6.6) New section on “Pressure Vessels and Equipment with Non-Volatile Liquid” which we are taking to mean Oil Pots and the like. This allows isolation of the relief protection during pump-down. Again, this has been the practice for years, so it’s nice that the IIAR has finally acknowledged it.

17.2.1) Power supply section reworded to no longer require separate power circuit for the NH3 detection.

17.3) Adds two new RAGAGEPs for NH3 detection design and testing “UL-61010-1 Safety Requirements for Electrical Equipment for Measurement, Control, and Laboratory Use or ANSI/ISA 92.00.01 Performance requirements for Toxic Gas Detectors.” I’ve reached out to my NH3 detector contacts and will follow-up with a separate post on the implications of these requirements.

17.7.1) Level 1 detection requirements revert to pre-PR1