“Failure is only opportunity to begin again. Only this time, more wisely.” –Henry Ford

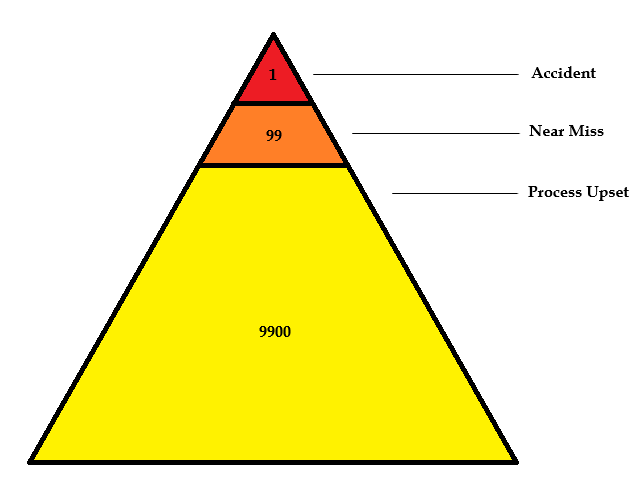

We often push PSM practitioners to perform Incident Investigations for fairly minor events in the hopes that the lessons learned from those minor incidents will stop the larger incidents from happening. This is, in part, due to CCPS (Center for Chemical Process Safety) guidance that, for every single catastrophic accident, there are typically nearly 9,900 minor issues / process upsets and 99 near misses.

So, if you only investigate the catastrophic incidents, then you are only acting on 0.010% of the opportunities available to you to improve your control over the process.

OSHA has promoted this idea as far back as a decade ago…

OSHA and industry have found that when major incidents have occurred, most of these incidents have included precursor incidents. Additionally, OSHA and industry (See CCPS [Ref. 41], Section 5, “Reporting and Investigating Near Misses” have concluded based on past investigations, that if employers had properly responded to precursor incidents, later major incidents might not have occurred. Consequently, anytime an employer has an “opportunity” to investigate a near-miss/precursor incident (i.e., an incident that could reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release) it is important that the required investigation is conducted and that the findings and recommendations are resolved, communicated, and integrated into other PSM elements/systems so a later major incident at the facility is prevented. …It is RAGAGEP to investigate incidents involving system upsets or abnormal operations which result in operating parameters which exceed operating limits or when layers of protection have been activated such as relief valves. (An example RAGAGEP for investigating incidents, including near-miss incidents is CCPS [Guidelines for Investigating Chemical Process Incidents, 2nd Ed.], this document presents some common examples of near-miss incidents). (OSHA, Refinery PSM NEP, 2007)

Going a step further, it’s often true that you can learn something about managing complex operations from businesses in entirely different fields. One field that I like to follow – in part because it’s endlessly re-inventing itself – is information technology.

Google recently published an article on their Post-Mortem culture, with a farcical worked-example that includes the movie “Back to the Future” and a newly discovered sonnet by Shakespeare. The practice of learning from their failures is actually part of their Sight Reliability Engineer handbook and you can read the entire chapter if it appeals to you.

“Failures are an inevitable part of innovation and can provide great data to make products, services, and organizations better. Google uses ‘postmortems’ to capture and share the lessons of failure…

… For us, it’s not about pointing fingers at any given person or team, but about using what we’ve learned to build resilience and prepare for future issues that may arise along the way. By discussing our failures in public and working together to investigate their root causes, everyone gets the opportunity to learn from each incident and to be involved with any next steps. Documentation of this process provides our team and future teams with a lasting resource that they can turn to whenever necessary.

And while our team has used postmortems primarily to understand engineering problems, organizations everywhere — tech and non-tech — can benefit from postmortems as a critical analysis tool after any event, crisis, or launch. We believe a postmortem’s influence extends beyond that of any document and singular team, and into the organization’s culture itself.”

Google’s Pre-Mortem Tool – Anticipating what can go wrong.

Google’s Post-Mortem Tool – Dealing with what actually went wrong.