Many, moons ago when I was a volunteer firefighter, we came up with a slogan for our crew: Perfection is Our Goal. Excellence will be Tolerated.

Page 11 of 13

For those of you that wanted the slides from the “How to prepare for an Inspection” presentation that was given by me at the 2017 DFW Regional RETA conference, the link is below:

2017 DFW Regional Conference PPT – Chapin 031317

Depending on your area you may get anywhere from five days up to six weeks notice for a scheduled inspection from the EPA. You aren’t going to create a compliant, living PSM/RMP program in that time frame but there are many things you can do to prepare the program you already have. Assuming you have a level 3 program in conjunction with a PSM program, here are three things you absolutely should do if you get notice of an inspection:

Synopsis from a 2012 post on another site:

What should you do if you get a notice of an EPA Risk Management Program inspection?

1) Know your material.

- The RMP Level 3 checklist that most EPA inspectors use is freely available online. Go through it and make sure you have these items covered in writing and that you know where to find them quickly.

- Check your documentation for accuracy: Every document you use to answer the questions in the RMP Level 3 checklist should be checked for accuracy. Are you doing the things the documents require in the way you say they will be done?

- Check for open recommendations. Whether they’ve been generated through Employee Participation, Incident Investigations, Process Hazard Analysis, Compliance Audits or any other source, make 100% sure that you have addressed every one of these recommendations. You don’t need to have every one of them closed, but you need a plan of action and a schedule for those actions in writing.

2) Prepare the staff – including yourself.

- Make sure everyone is aware that an inspection is going to happen.

- You don’t want to be tripping over contractors so you may wish to schedule their work at times that don’t coincide with your inspection.

- Remind your staff to “GO TO THE DOCUMENTS” in response to any PSM/RMP question.

Q: “How do you drain this oil pot?”

A: “With this written procedure.”

Q: “How much ammonia is in the system?”

A: “This inventory calculation sheet has the information you are asking for.”

- Handle this as a professional learning opportunity and you’ll do much better. Rather than having a surly demeanor and saying “What do you want?” to an inspector, why not something more like “We put a lot of effort into our PSM/RMP program to protect our employees and the environment. We’re really looking forward to this opportunity to show you all the hard work we’ve been doing and perhaps find some ways we can further improve it in light of your experience.” Now you’ve complimented the inspector and expressed your company’s desire to meet the goals of the program – nobody loses there.

- Relax: Remember they are auditing a program – not the people who implement it. It’s important that you take the inspection seriously but it’s not the inquisition. Don’t relax too much: I know of several inspections that went downhill rapidly because the staff were treating the inspection as a joke.

- Put yourself in their shoes for a second. Inspectors are generally good people trying to do a good thing – treat them as professionals. There are appropriate venues to vent your feelings on the federal or state government – the inspection is not one of them. Inspectors are used to being treated awfully so why not be the exception and treat them as a welcome guest?

- On the flip side – STAND YOUR GROUND. Support your program and your compliance efforts with RAGAGEP (Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practices) so the inspector is left to argue with the CCPS or the IIAR rather than you personally. Often inspectors will want to see something a certain way. When you are having an issue meeting their demands, ask them exactly what portion of the law they are referring to. PSM/RMP is a performance oriented standard – they picked the destination but your company gets to pick the path you take to that destination.

3) Prepare the facility

- Part of the inspection will include a site tour. This is no different than a visit from your mother in law – you will want to put your best foot forward.

- Plan out your route so the inspector gets to see everything they need to see while showing the facility in the best light.

- Do some dusting, painting, re-labeling and tagging as needed. A little bit of housekeeping goes a long way in establishing good will.

- LOOK at your system. A dented drain pan will draw questions about “struck-by hazards”, a fresh weld and unpainted pipe will draw questions about Management of Change, frost on insulation will draw questions about Corrosion Under Insulation and Non-Destructive Testing, etc. Be prepared for these questions and have ready answers.

The steps above WILL prepare you for an EPA inspection and they WILL improve your results. What they can’t do is cover up a program that has been neglected for years, but if you are reading this then that’s probably not your situation. Almost any program that has not been completely neglected can be improved and polished enough to pass most EPA inspections with the help of a great compliance consultant.

If you find yourself in need of some advice, some pre-audit assistance or a compliance audit / gap analysis, you can always call on your favorite resource for some assistance before the inspection. I would love to hear from you and help you prepare. You don’t have to be in this alone!

My favorite part of PSM/RMP implementation has always been Incident Investigations. Not because of any morbid curiosity, but simply because it’s where we learn how to improve our processes and the PSM/RMP programs we use to control them.

A friend and colleague of ours, Bryan Haywood of SAFTENG.net recently posted an EPA Citation Summary regarding a release of NH3 that hospitalized a facility worker.

Here’s a portion of the summary:

On April 22, 2016, maintenance work was performed at the Facility. Specifically, a maintenance worker replaced a belt on a spiral freezer. The worker utilized a written standard operating procedure (“SOP”) in performing the work. To safely perform the belt replacement maintenance the worker turned off the spiral freezer, which was in defrost mode at the time. The defrost cycle was interrupted when the freezer power was turned off. According to Respondent and the spiral freezer manufacturer, the spiral freezer requires routine and uninterrupted defrosting for proper performance.

Upon completion of the maintenance work, the worker restored power to the spiral freezer, which returned to a defrost mode. The following day, April 23, 2016, the spiral freezer was re-started and returned to use. Workers operating the spiral freezer were unaware of the interruption to the defrost cycle due to the belt replacement that occurred the previous day.

During the loss of power, caused by the maintenance work, and subsequent interruption of the defrost cycle, gas built up in the ammonia system relating to the spiral freezer. Soon after the spiral freezer was returned to service, hydraulic hammering, caused by the built-up gas, began in the ammonia piping related to the spiral freezer. The hammering weakened the weld on an end cap to the point where it failed. The end cap of a 16″ ammonia pipe fell off onto the protective floor spilling ammonia into a production area where employees were present. Ammonia alarms sounded and the Facility was evacuated.

Upon mustering at designated points outside the Facility (per the Facility emergency plan) it was determined that one employee was missing. Pursuant to the emergency plan predesignated workers entered the Facility to search for the missing worker who was found unconscious near the ruptured ammonia pipe. The emergency plan identified that Facility emergency responders needed self-contained breathing apparatus (“SCBA”) equipment to enter the Facility during releases of ammonia. SBCA equipment was available for all emergency responders at the Facility. One employee, an emergency responder, however, only put on an air purifying respirator (“APR”) to enter the building.

Eight employees were sent to the hospital of whom seven were released after observation and/or treatment for non-serious injuries. One employee, who was directly adjacent to the ammonia spill, required hospitalization. Doctors induced a coma and the worker was attached to a ventilator to provide breathing assistance for several weeks. The employee was subsequently released from the hospital.

Among other things that could have prevented this release scenario are two that the EPA didn’t cite: Training and Communication.

Training: A basic understanding of how refrigeration systems operate should have ensured that the facility didn’t restart this unit until it was equalized to the system.

Communication: It’s very possible the people that restarted the system were completely unaware of the work that had been done and of the possible effects of the prolonged shutdown

That said, there are always changes that can be made to procedures to add further administrative controls to situations like these. Due to this ongoing issue, we’ve decided to improve the existing Air Unit RESOP template by making the following changes:

- In the Startup phase, we’ve changed the wording of the step that opens the suction valves to include a warning that if these valves are closed, they should be opened SLOWLY

- In the Startup phase, we’ve modified the step that enables the “Run” or “Auto” mode in the control computer to check first that the unit Coil Pressure is within 30PSIG of the desired Suction Setpoint before allowing the Control Computer to take control.

- In the Shutdown phase, we’ve advised that if the unit is in the Defrost mode, the Defrost operation be allowed to conclude before stopping the unit with the Control Computer.

All future SOPs written based on these templates will use these modifications. If you have a program written with older versions of these templates, consider the following steps:

- Discuss this issue with your Operating staff so they understand the possible ramifications of an ill-timed shutdown or an improper startup.

- Consider updating your SOPs to include these changes or having your PSM Service Provider make these changes for you.

As always, if you are using these templates (or a program based on them) the updated AU RESOP template is on the Google Shared Drive with a 042017 revision date for your convenience.

Please don’t hesitate to contact me if we can be of any assistance with these revisions.

— Link to PDF of original CAFO

Over the past few years we’ve seen an increase in the number of companies that use a 3rd party service to qualify their contractors. Often, these services screen the prospective contractor for their safety record / programs, insurance history / coverage, and financial stability. It’s common to see facilities believe that these contractor qualification services are covering their PSM/RMP Contractor obligations, but this is rarely the case. Let’s review the PSM/RMP requirements regarding Contactors – starting with the facility obligations – to see why:

1910.119(h) Contractors.

1910.119(h)(1) Application. This paragraph applies to contractors performing maintenance or repair, turnaround, major renovation, or specialty work on or adjacent to a covered process. It does not apply to contractors providing incidental services which do not influence process safety, such as janitorial work, food and drink services, laundry, delivery or other supply services.

This section covers which contractors are covered under the PSM/RMP rules. Since nearly all of these Contractor Qualification services cover all contractors, you are usually well covered here.

1910.119(h)(2) Employer responsibilities.

1910.119(h)(2)(i) The employer, when selecting a contractor, shall obtain and evaluate information regarding the contract employer’s safety performance and programs.

Every Contractor Qualification service we’ve seen covers this area quite well – in fact, it’s the reason these services exist. 1910.119(h)(2)(ii) The employer shall inform contract employers of the known potential fire, explosion, or toxic release hazards related to the contractor’s work and the process.

1910.119(h)(2)(iii) The employer shall explain to contract employers the applicable provisions of the emergency action plan required by paragraph (n) of this section.

Here we get our first compliance issue. Contractor Qualification services do not possess this information and cannot provide it to the contractor. Let me quote the 2009 Petroleum NEP to show you why this MUST be done by the facility itself:

Compliance Guidance: To assist in determining the applicable known potential fire, explosion or toxic release hazards that the host employer must inform the contract employers about, CSHOs should examine the host employer’s PHA. The PHA must identify the hazards of the process – 1910.119(e)(1) and (e)(3)(i). At a minimum, the hazards identified in the employer’s PHA which are applicable to the contractor’s work must be passed (“informed”) from the host employer to the contract employer – 1910.119(h)(2)(ii). In turn, the contract employer must then instruct its employees on the known potential fire, explosion or toxic release hazards of the process (1910.119(h)(3)(ii)), including, at a minimum, those hazards identified in the host employer’s PHA which are applicable to the contractor’s work.

As you can see, this requires a deliberate and thoughtful analysis of the work the contractor will do and the hazards present by that work – and the area of the process they will be working on. A cookie-cutter Contractor Qualification service cannot provide this service so you need to make sure your program does.

1910.119(h)(2)(iv) The employer shall develop and implement safe work practices consistent with paragraph (f)(4) of this section, to control the entrance, presence and exit of contract employers and contract employees in covered process areas.

Again, a Contractor Qualification service cannot provide this service – this is a facility level requirement that establishes and implements the procedures required under the Operating Procedures element.

1910.119(h)(2)(v) The employer shall periodically evaluate the performance of contract employers in fulfilling their obligations as specified in paragraph (h)(3) of this section.

1910.119(h)(2)(vi) The employer shall maintain a contract employee injury and illness log related to the contractor’s work in process areas.

While a Contractor Qualification service can maintain some general information on the contractor in general such as injury rate and accident history, it will not know about the specific performance of a contractor at your facility – at least not as well as your own people will.

Next, we move on to the PSM/RMP responsibilities of the Contractor…

1910.119(h)(3) Contract employer responsibilities.

1910.119(h)(3)(i) The contract employer shall assure that each contract employee is trained in the work practices necessary to safely perform his/her job.

1910.119(h)(3)(ii) The contract employer shall assure that each contract employee is instructed in the known potential fire, explosion, or toxic release hazards related to his/her job and the process, and the applicable provisions of the emergency action plan.

1910.119(h)(3)(iii) The contract employer shall document that each contract employee has received and understood the training required by this paragraph. The contract employer shall prepare a record which contains the identity of the contract employee, the date of training, and the means used to verify that the employee understood the training.

While a Contractor Qualification service can certainly request this documentation, what’s usually acceptable to the Contractor Qualification service is a generic “statement” on training, not the very specific training required based on the information provided under 1910.119(h)(2)(ii-iii).

1910.119(h)(3)(iv) The contract employer shall assure that each contract employee follows the safety rules of the facility including the safe work practices required by paragraph (f)(4) of this section.

A Contractor Qualification service can certainly ask the contractor to provide a pledge that they will follow the safety rules / practices at the facility, but this can only really be proven through direct on-site examination of the contractor on a regular basis.

1910.119(h)(3)(v) The contract employer shall advise the employer of any unique hazards presented by the contract employer’s work, or of any hazards found by the contract employer’s work.

A Contractor Qualification service will ask the contractor to provide this information, but very often the nature of the work (and the tools used to perform it) change during the project. Again, only direct on-site examination of the contractor on a regular basis can ensure that the contractor is compliant with this requirement.

I hope this review has helped you understand how Contractor Qualification services can be useful to meet some PSM/RMP obligations, while showing you how they cannot replace your entire PSM/RMP Contractor element.

Note: See December 2019 Update.

We’ve delayed updating our templates or offering updated programs that reflect the proposed EPA RMP changes for several reasons. Our patience has been well-rewarded:

The EPA has proposed to further delay the effective date to February 19, 2019. This action would allow the Agency time to consider petitions for reconsideration of this final rule and take further regulatory action, which could include proposing and finalizing a rule to revise the Risk Management Program amendments. This action would allow the Agency time to consider petitions for reconsideration of this final rule and take further regulatory action, which could include proposing and finalizing a rule to revise the Risk Management Program amendments.

DATES:

Comments. Written comments must be received by May 19, 2017.

Public Hearing. The EPA will hold a public hearing on this proposed rule on April 19, 2017 in Washington, DC.

ADDRESSES: Comments. Submit your comments, identified by Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OEM-2015-0725, at http://www.regulations.gov.

As always, we’ll keep you up to date on any changes to the PSM/RMP rules AND appropriate RAGAGEP.

Many of the readers of this website have PSM/RMP programs written using our Open-Source PSM templates. The members of our community have read-only access to the Google Drive templates directory where the newest revisions and updates to those documents are housed. While we’ve kept a “Change Log” in the root directory of that shared drive for a long time, we’ve recently decided to make a blog post about every template change to raise awareness of these changes and assist those of you who want to continue updating your program. What follows is our first blog post along those lines:

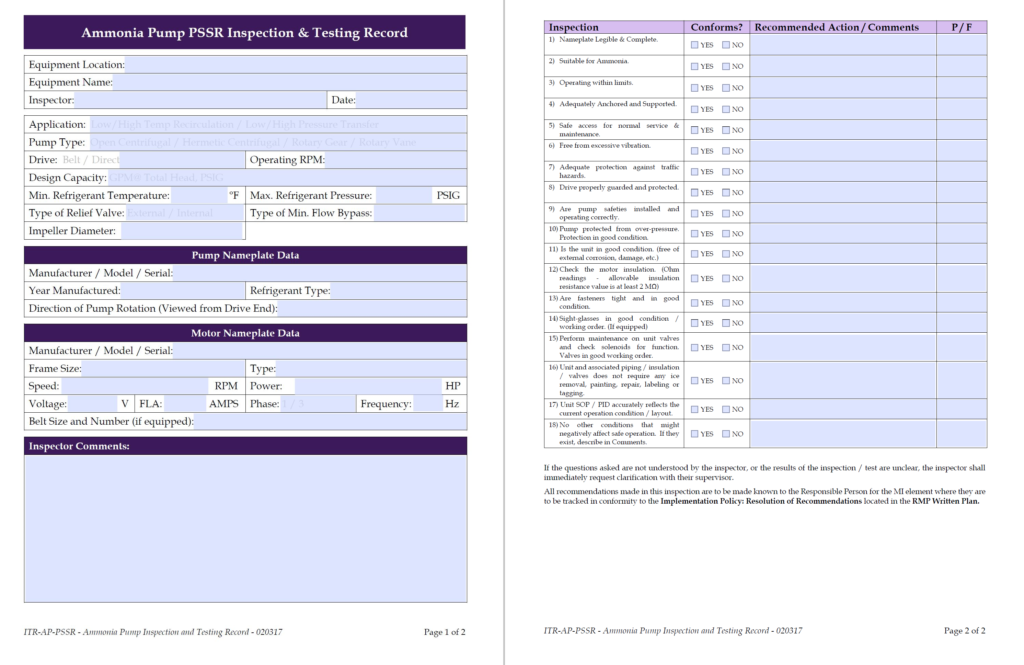

PDF “Form” versions of commonly used MI & PSSR Forms

Back in July of 2016 we first introduced documents to our PSM Template system called ITR-PSSR forms. These “Inspection Test Reports for Pre-Startup Safety Reviews” provided a standard format for new equipment documentation and safety checklists that replaced the B109 form that some people use. Unique forms were provided for common subsystems and equipment, such as:

- Ammonia Pumps

- Air Units

- NH3 Detectors

- Evaporative Condensers

- Heat Exchangers

- Machine Rooms

- Piping Sections

- Purgers

- Pressure Vessels

- Compressors

- Ventilation Systems

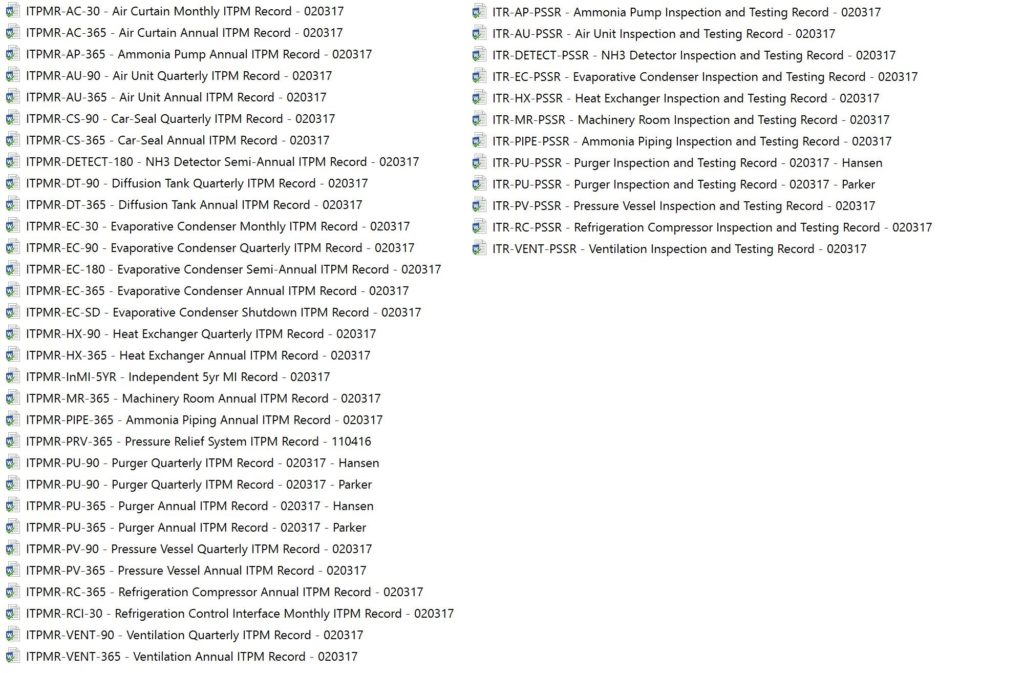

In September of 2016, we provided PDF versions of these as “PDF Forms” that were usable for data entry. At some point, those files were apparently removed or lost. I recreated those PDF forms today for all the ITR-PSSR Forms.

I also converted each of the ITMPR forms. These “Inspection Test & Preventative Maintenance Reports” form the basis of our Mechanical Integrity program documentation. Both the ITPMR and ITR-PSSR forms are now on the Google Drive in their respective PSM element folder. The revision dates of the PDF reflect the revision date of the original Word document.

Can I use these in my program?

If you use our templates, or we wrote the program for you in the last two years using these templates, then the answer is Yes, but how easily depends on the age of your program.

If your program is newer than September 2016: Those of you who use our PSM/RMP templates to create their own programs – or those of you who have a program we created post September 2016, can drop these updated forms directly into your program.

If your program is older than September 2016: If your program was created before September of 2016, the ITR-PSSR forms can be added to your program as alternate PSSR documentation. Your MI documentation were called ITR forms at the time – not ITPMR. To replace the ITR forms with the updated ITPMR forms you can do one of two things:

- Replace every mention of ITR with ITPMR in each of your element guidelines/written plans, SOPs, MI schedules, etc.

OR

- Write a memo / Letter to File explaining that ITR and ITPMR mean the same thing in your program and can be used interchangeably.

Regardless of the age of your program, make sure you conduct a brief training with your operators on these new forms before your implement them.

Here’s a list of the updated files that now have PDFs available on the Google Drive:

You may have recently heard a headline that OSHA is losing their right to cite you for something that happened more than six months ago. I’ve heard a disturbing amount of people tell me that this means that many PSM issues can be ignored, because – as long as they “get away” with it for six months – they are uncitable. From the vantage point of safety, this is absurd thinking. Taking such a risk, simply because you are unlikely to be caught, would be the equivalent of not wearing your seatbelt because you aren’t particularly likely to get in a car accident in any given drive. The difference is that when things go wrong in Process Safety, the results are usually far worse than the average car accident.

That said, let’s set aside SAFETY for a second, and look at where this idea comes from:

The Occupational Safety & Health Act of 1970 states in 29USC658(c) that “No citation may be issued under this section after the expiration of six months following the occurrence of any violation.”

Years ago, however, OSHA proposed and published a rule stating that “ongoing obligations” required some records to be kept longer – specifically injury and illness records. They stated, in part: “The OSH Act’s statute of limitations does not define OSHA violations, or address when violations occur, nor does the language…preclude continuing recordkeeping violations.” OSHA has actually issued several citations for items that were past the six month statute of limitations, in once case for an ongoing MOC violation that occurred over twelve years ago.

OSHA lost several court cases with this “ongoing violation” issue. The House recently passed a CRA resolution to throw out this rule. Assuming the CRA continues, OSHA will not only continue to lose in court, but they will be barred from issuing a “substantially similar” rule in the future. This has led to a widespread belief that PSM violations that occurred over six months ago will no longer be citable. While that may be technically true, the reality is that they will still be citable as long as OSHA does the legwork to write the citations correctly.

For my example, let me use one of the most common problems I see in Compliance Audits: A recommendation (from PHA or former Compliance Audit) from well over a year ago regarding the identification of surface corrosion on ammonia piping that recommends an increased frequency of inspections and/or remediation of the protective coating.

If that recommendation was unaddressed, in the past OSHA would often cite the PHA or Compliance Audit element from which the recommendation came. Assuming that they are now limited to six months, and the recommendation is older than that, OSHA can NO LONGER cite you for that violation.

Super. Congratulations… But, if OSHA could cite you for not following up on the recommendation, then it’s likely because the pipe is still showing signs of corrosion. That being the case, they CAN cite you for a 1910.119(j)(5) deficiency because the pipe IS rusted during the inspection.

Put a simpler way – they can use the violation from the past to lead them to a violation occurring in-the-moment. Nearly ALL PSM citations can be rewritten to in-the-moment violations.

Furthermore, although the old recommendation can’t be used for a citatable situation directly, it is PROOF POSITIVE that the employer was AWARE of the hazard.

Worse yet, most EPA violations are only subject to the 28USC2462 five-year statute of limitations. It’s not like an OSHA CSHO or AD can’t pick up a phone and call the local EPA office.

TLDR: The end result of OSHA losing their ability to cite for something in PSM that happened over six months ago: Nothing, really.

In refrigeration we use PSI (pounds per square inch) as a measure of pressure, but we often show it on different scales. PSIA (pounds per square inch absolute) is a scale that shows the pressure relative to a pure vacuum. PSIG (pounds per square inch gauge) is a scale that shows the pressure relative to the ambient atmospheric pressure at sea level.

The difference between PSIA and PSIG is a little less than 15PSI due to the atmospheric pressure. That doesn’t seem like a lot of pressure, does it?

Here’s a video showing a cannon that uses that atmospheric pressure to destroy a watermelon.

The incident we are discussing today is from a recent ruling in the United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit where they recently denied a petition for review in the case of “DANA CONTAINER, INC. v. SECRETARY OF LABOR.” While this particular citation concerns “Permit Required Confined Spaces,” the lessons are applicable to all OSHA rules.

The case arose after toxic fumes in a large container knocked out a man who was working inside it. From the ruling:

In the cold early morning hours of January 28, 2009, one of Dana’s supervisors, Bobby Fox, was on the third shift along with former employee Cesar Jaimes. Fox was working on a trailer and encountered a problem with a clogged valve just as he was about to begin the mechanical cleaning process. Disregarding the safety rules, he entered the tank prior to cleaning it, without attaching himself to the retrieval device or following the entry permit procedures. After a short while, Jaimes looked inside, saw Fox unconscious in a pool of chemical sludge, and called the Summit Fire Department. The firefighters hoisted him out, rinsed off the chemical residue, and transported him to the hospital. Fox was diagnosed with “Syncope and Collapse, Toxic Effect of Unspecified Gas, Fume, or Vapor” (i.e., fainting).

While the employee was rescued by the local fire department, his employer, Dana Container, was cited for Willful violations by OSHA and has been fighting those citations – through an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), then the OSHA Review Commission and now through the Circuit Court.

Here is a proven three-step plan to get Willful OSHA citations

1) Have a supervisor break the rules: The employer tried to prove that the unsafe actions were “unpreventable employee misconduct” such that the employer was unaware of the issue. OSHA is required to prove that the employer knew about the problem.

In this case, the supervisor’s knowledge can be imputed to the employer… This path for imputing knowledge is common in employment law. When an employee is acting within the scope of her employment, her knowledge is typically imputed to the employer… Conduct is “within the scope of employment when [it is] ‘actuated, at least in part, by a purpose to serve the [employer],’ even if it is forbidden by the employer.” Here, Fox knew that he was violating the rules when he entered the dirty tank in order to kick loose a stuck valve so that he could then drain the tank. His act was in furtherance of Dana’s tank cleaning business.

2) Have a track-record of failing to follow your own safety programs: OSHA was able to show that the employer should have been able to foresee the supervisor misconduct because they knew (or should have known) there were long-standing issues with their program:

There was evidence showing that nearly all of the tank entry permits at Dana’s Summit facility contained errors or omissions. Some indicated that the entries had exceeded the maximum duration of 20 minutes by over an hour. Others had other flaws: for example, they lacked the requisite air monitoring results; they failed to show the duration for which the permit was valid; they indicated that employees had not reviewed material safety data sheets (or had no information about review); and they failed to name either the entrant or the entry attendant. Whether these errors and omissions occurred because the employees were violating entry procedures or if they reflected only recording problems, there is no evidence that the Facility Manager followed up on the deficiencies. The Commission was therefore justified in concluding that there was a failure to enforce Dana’s safety program… The Commission was entitled to find that the uncorrected permit violations exhibited a pattern of disregard for the rules at Dana. Even in the face of a robust written program, lax disregard of the rules can send a message to employees that a company does not make safety a priority. In such an environment, conduct such as Fox’s is reasonably foreseeable… Dana’s effort to persuade us that the Commission erred by rejecting the “unpreventable employee misconduct” defense also falls short. To use the defense an employer must show that it took steps to discover violations of its safety rules and that it effectively enforced the rules when violations were discovered.

3) Have a shaky track record on enforcement of your own policies: Dana cited a OSHA Review Commission case holding that an employer can demonstrate that the willful conduct of its supervisory personnel should not be imputed to the employer if the employer can demonstrate a good faith effort to comply with the standard.

The Commission…found that although, on the one hand, Dana had work rules that were communicated to its employees and had submitted evidence of three instances of disciplinary action, on the other hand the facility manager had never disciplined an employee for improperly completing permits or for the violations apparent on the face of the permits. The Commission concluded that Dana had therefore failed to take action when violations of safety rules were plain, as would have been required in a good faith effort.

Working backwards, you can avoid willful citations by:

- Establishing clear, compliant policies on OSHA rules.

- Requiring Supervisors to be responsible for the implementation of our policies, the enforcement of those policies and the documentation of our adherence to those policies.

- Requiring the Safety Department to periodically audit the compliance to our policies of field supervisors and personnel.

P.S. Bonus: It’s never a good idea to get in the news:

“A local TV news crew broadcast the rescue that morning, and OSHA inspector Jami Bachus happened to see it before heading to work. She volunteered to inspect Dana’s facility and did so, arriving at the Summit station within three hours of the accident.”