Let us help you make sense of PSM / RMP!

We’ll be having an open-enrollment PSM class in Burleson, Texas July 8th-11th 2025.

You can get more information on the class with this link.

We hope to see you there!

Chill - We Got This!

Let us help you make sense of PSM / RMP!

We’ll be having an open-enrollment PSM class in Burleson, Texas July 8th-11th 2025.

You can get more information on the class with this link.

We hope to see you there!

There are a lot of choices out there for fixed Ammonia Detection these days. Common brands include CTI, Manning / Honeywell, Danfoss, Bacharach, Draeger, Hansen, and CoolAir.

Obviously if you are installing a new detector in a General Duty or PSM/RMP covered process, you want to perform an equipment-level PSSR (pre-Startup Safety Review) for the detector. However, a common question we get is “does changing from one brand to another require an MOC?”

The root of this question is usually an attempt to justify the “change” as a “Replacement in Kind” and therefore avoid the paperwork of an MOC. But an MOC is not about PAPERWORK. An MOC is about thinking through the desired change (in a structured way) to see where problems can arise.

Put another way: Implementing the MOC procedure is how we answer the question of whether or not we need to document how we manage the change.

Let’s consider some things that might change when we replace one detector brand for another.

Sensor Type: Electrochemical, IR, Catalytic Bead, etc. Each of these types of sensors has benefits and drawbacks based on the conditions they are used for and in. If you are changing technologies, how does that change affect your process?

Sensor Range: Obviously the range of the sensor has an impact on how it works in your system. Replacing a 1-500ppm sensor with a 1-250ppm sensor without altering the system programming will report the wrong chemical concentration.

Signal Type / Range: Most sensor setups work on a 4-20mA signal, but some use Modbus or proprietary methods. You need to match your technologies or provide signal conversation.

Enclosure Rating / Environmental Considerations: Some sensors are subject to difficult environmental conditions such as blast-freezers and wash-down areas. You need to make sure that the sensor is suitable for the conditions you will expose it to.

Detector Placement: Manufacturer’s often provide recommendations on the height they want their detectors placed at. Make sure you are addressing those recommendations. If you are moving the Detector, are there any guarding considerations in the new location?

Inspections, Tests & Maintenance: Manufacturers have different inspections, tests and maintenance types and schedules. You must make sure you align to the manufacturers recommendations.

Bump Tests / Calibrations: Both the calibration method & frequency must be considered, including any unique calibration equipment and gases.

Conclusion: So, it’s possible that swapping a detector might well be a “Replacement in Kind” but there are a lot of things to consider before you arrive at that decision. You should use your MOC process to see if you need a formal, documented MOC.

“Time Waits for No one…”

The Issue at hand

When I first started in NH3 refrigeration, you could pick up the phone, talk to your parts-guy, and get a replacement valve quickly: often the same day, but usually within a business day or two. While you were waiting for the part, you either operated the equipment manually (requiring a temporary SOP / MOC) or shut the equipment down during the wait. We call the time between when you order something and when it arrives, lead-time.

Because lead-times *were* short, parts inventory at most facilities were kept fairly low – usually limited to what would stop production. If you could get what you needed in a day or two, why keep it on the shelf, unless you were losing 20k+ an hour in downtime?

The situation has changed around us, and I’m not sure we’ve all thought through the implications of the current supply-chain issues. Lead-times have grown substantially in 2021 and, while relief is promised in the second half of 2022, these long wait times for equipment and components have the potential to adversely affect our Process Safety.

Current Lead Time estimates

| Equipment / Component | Lead-Times in Weeks* |

| Valves, Shutoff and Control | 14-24 |

| Valves, Relief | 12-20 |

| Vessels | 14-24 |

| Condensers | 14-16 |

| Compressors | 16 |

| Air Unit / Evaporators | 36 |

| Heat Exchangers | 14 |

*Typical for NH3 components. Varies by brand. Some halocarbons lead-times are even longer.

How can this affect Process Safety?

When you don’t have a critical spare part, and won’t have one for several months, production demands are likely to force you to operate your equipment in “temporary” modes. Here are a few thoughts:

What should I do?

“The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality…” –Max DePree

Well, the first step is to start a discussion with your skilled technicians and make sure they understand the environment we’re all working in. Here are some points for discussion, and further actions to take:

RC&E can assist you with your parts and spares. Click Here for our Line Card. Call Dennis Vaught 817-210-1957 or email him at dvaught@rce-nh3.com

The issue: A facility with an ammonia refrigeration system notes that their HPR level is rather low, and they are considering ordering some ammonia to get back to the levels they “used to have.” The thinking is that they need to add to the ammonia charge to make up for ammonia that was lost over the years.

Before you go too far, a good question to ask is: Did I lose ammonia? Or is it just somewhere else in my system?

What if you didn’t lose it?

Did you add equipment without your MOC addressing if this required an inventory adjustment? Did you change recirculator vessel levels which make the HPR look low even though the ammonia is still out in the system? Has someone been mucking with the HXV’s or TXV’s, so you are “brining” coils? These are common issues, but the most likely culprit is seasonal variation.

If it’s August in Texas, it’s likely that your system is running about as hard as it will ever run. That means that the NH3 isn’t just hanging out in your vessels, but out in the various heat exchangers (and their piping) doing its job. The “good old boy” method of testing this was to wait until the cool of the night, shut down the liquid feed to your “load,” and check the vessel levels after the NH3 came back.

A more “modern” method is to use an inventory spreadsheet and adjust the levels in the heat exchangers to reflect the summer load. The intricacies of doing either of these are better dealt with in the real world rather than a blog-post, so let’s assume you have already checked this and you actually do need ammonia. (Note: if you need assistance with either of the above, we can certainly assist you, just give us a call)

Ok, maybe we did lose it!

If you look into the situation and find out that you actually do need ammonia, there are a few considerations you should think of BEFORE you order that truck and start preparing for delivery.

Justifying the charge

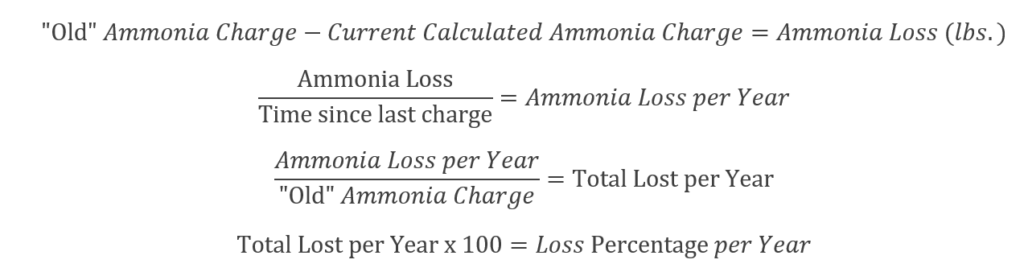

Assuming you didn’t have some sort of incident that clearly explains why you need ammonia, we should figure out how to justify the amount we’re adding. Most losses are easily justified by establishing a “loss rate” and comparing it to accepted norms. This acceptable loss would be caused by normal maintenance, auto-purgers, and fugitive emissions.

In my opinion, anything less than 5% is good. 2-3% is excellent. For what it’s worth, the IIAR has stated that up to 10% loss a year is “reasonable.”

A loss rate of 3% or less a year can easily be explained from normal maintenance, auto-purgers, and fugitive emissions.

This is easier to explain with a worked example from a friend. In this case, their inventory level is supposed to be 5,800lbs. When they updated their inventory sheet to reflect the actual conditions at the facility, they saw a calculated current charge of 5,000lbs reflecting an 800 pound loss. That loss occurred since their last charge 5 years ago.

This percentage is easily explainable from maintenance and other fugitive emissions, and it’s also quite reasonable.

If you take the time to figure out the math above, and then document your calculations to justify your NH3 charge, it helps avoid unpleasant assumptions on the part of the EPA and OSHA in any future inspections.

If an auditor comes in and sees an ammonia delivery receipt, a documented rationale why the ammonia was needed, the SDS of the chemical charged, and you have a compliant charging procedure, it would be very unlikely that the charging process would be questioned further.

Of course, if your math shows a high leak rate, then you had better get an incident investigation going and figure out what’s wrong!

P.S. – To assist in this effort, Scott updated the Ammonia Inventory example template has been updated to help automate this process. Just enter the old value, newly measured value, and time (in months) since last charging and you have a 1-page report on the % loss per year. We hope this helps. The file can be located at: \ PSM-RMP Program Templates \ 03 – Process Safety Information \ Optional Resources \

“Smart people learn from their mistakes. Wise people learn from the mistakes of others.”

Or, in PSM terms: Incident Investigation is how you become smart. Process Hazard Analysis is how you become wise.

Yesterday, a horrific explosion occurred in the port of Beirut, Lebanon. This morning it is being reporting that over 100 are dead, over 4,000 are injured, and up to 300,000 are homeless. Estimates of the economic damage have been as high as five billion dollars.

Beirut, Lebanon Explosion 08/04/20

It is believed that the explosion was the result of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate stored at the port. The authorities will now have to try and piece together what happened to see what they can learn from this incident.

Beirut, Lebanon Explosion Aftermath 08/04/20

In PSM terms, this is where we implement the Incident Investigation element. Refer back to that earlier quote, “Incident Investigation is how you become smart.” One of my first mentors put it another way: “Wisdom is healed pain.” It is right and proper that we learn from the mistakes we make, but there is a better way: Learn from the mistakes of others so you don’t repeat them!

Al Jazeera is reporting that the chemical storage was known about for seven years, and while the port authorities asked for assistance in dealing with the dangerous situation SIX TIMES, they did not receive a response. It appears that the authorities in Beirut had the information they needed to KNOW they had a hazards to address for many years.

The dangers of Ammonium Nitrate explosion are WELL KNOWN. Check out this older article on the events in West, Texas – or check out the pictures I took there after the explosion. (Note, according to the Al Jazeera timeline, the improper storage of this chemical in Lebanon began right around the time of this incident in America.)

Ammonia Nitrate explosion damage in West, Texas (2013)

A proper PHA prevents incidents. In the PHA process, we Identify hazards, Evaluate those hazards, and then Control those hazards.

A timely Process Hazard Analysis would have shown OBVIOUS problems with Facility Siting, RAGAGEP compliance, and equipment / facility suitability. It appears that in Beirut, the port officials informally identified at least some of the hazards, and to some degree they analyzed them. Those responsible in Beirut had AMPLE opportunity to CONTROL the hazards but chose not to – for reasons we don’t yet know.

Put another way, because they did not accept their responsibility to perform a Process Hazard Analysis, they now have to accept their somber duty to perform an Incident Investigation.

Incident Investigation is how you become smart. Process Hazard Analysis is how you become wise.

Are there any issues in your facility that you are aware of that you haven’t yet addressed? Consider this tragedy in Beirut as a reminder to take action on them. There’s no time like the present!

P.S. There are large Ammonia Nitrate stockpiles all over the world. When stored properly it is very, very safe. But storing it next to a fireworks warehouse in a vault that wasn’t designed for it is begging for a disaster.

— Update: The Times of Israel quotes Lebanese Prime Minister Hassan Diab as saying: “What happened today will not pass without accountability. Those responsible for this catastrophe will pay the price.” With respect, no, they won’t pay the price.

The people that died paid the price. The loved ones of the deceased, the people that were injured, and those who are now homeless are paying the price. The people responsible may pay a price, but it’s unlikely to be as severe as the one paid by those who had no part in the series of errors that lead to this catastrophe.

(What to do when you are suddenly responsible for years of Process Safety neglect.)

It’s a scene I come across time and time again: a newly assigned PSM/RMP coordinator staring at me with shock as we progress through their Compliance Audit, Process Hazard Analysis, or 5yr Independent Mechanical Integrity Inspection.

“I didn’t know things were this bad!” they’ll say under their breath, once the situation starts to become a little clearer to them. You can imagine them standing at the bottom of a deep, dark hole wondering how they’ll ever make it back to fresh air and bright sunshine they thought was all around them just a few hours ago. For those of you that have read my previous post on the “Stages of PSM Grief,” this is the moment they are breaking past the Denial stage.

It can be heartbreaking to watch the mixture of Anger, Bargaining and Depression, especially if you remember what it felt like to be there yourself.

Often, I will have to re-assure them that this is just the start of the process and the beginning isn’t going to be fun. Sometimes I’ll quote Winston Churchill.

What’s really important is that we understand there will be a way out if we remain calm and plan intelligently. Unsurprisingly, you need a process to address Process Safety issues.

So, let’s start planning our escape! We’re going to move slowly at first, with ever-increasing confidence, and once we get rolling we’re going to start seeing daylight.

Here’s how our progression will look:

Part 1: Assess the situation

Obviously, if you are in the middle of (or have just gone though) an audit or inspection, you’re well on the way! If you are recently assigned to this coordinator role and you don’t have a recent compliance audit, PHA, and MI report, then these are good places to start.

Assessment is really two parts which can share the same ground.

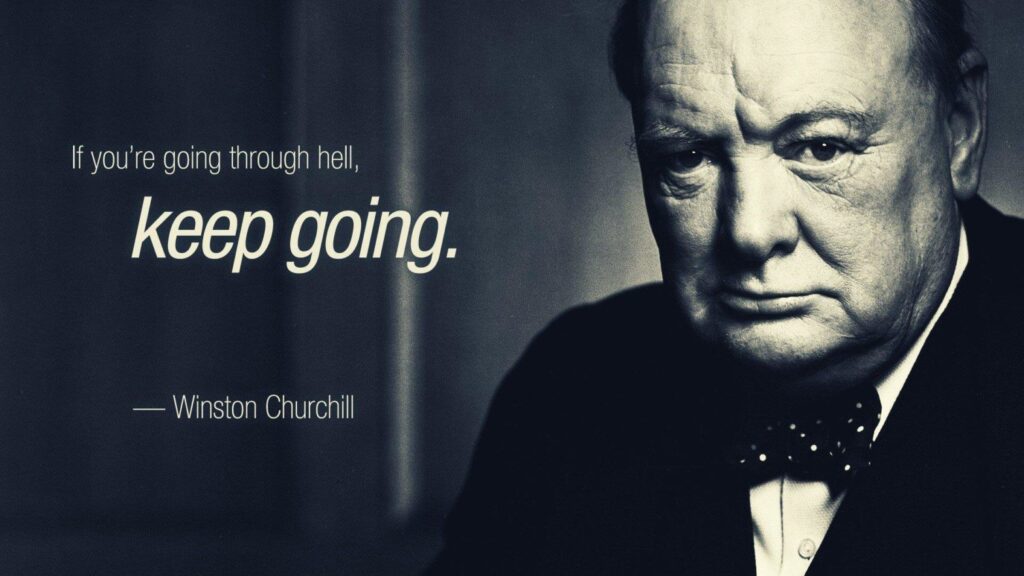

I can’t stress this enough – being compliant is not some lofty place. It is the bare minimum of safety allowed under the law. How far past “my company isn’t violating federal and state law” you want to go depends a lot on the culture of your organization. For example, companies with a brand to protect tend to aim a lot higher than those that don’t. Companies that are barely making ends meet tend not to have a lot of resources to bring to bear on things that aren’t strictly required.

Recently, based on a conversation with colleagues, I half-jokingly formulated what I called the Haywood / Chapin Process Safety performance scale as a visual tool. Note that you get a score of zero for being compliant because that’s the baseline. We’re not going to go around congratulating each other for not violating Federal and State laws. Additionally, we aren’t going to give ourselves any credit for trying – only for results: Safety & compliance aren’t kindergarten so we aren’t giving out participation trophies.

Note: It’s common at this point to try and figure out how the company got themselves in this hole, but there is usually very little of value that comes out of this conversation. If the same people, and the same processes are in place, don’t expect different results unless they are willing to change. Don’t get your hopes up just because people want to change. What matters is if they are willing to put in the work to change. If only wanting to change was enough to effect change, nobody (including me) would be carrying around a few extra pounds.

Part 2: Prioritize the issues

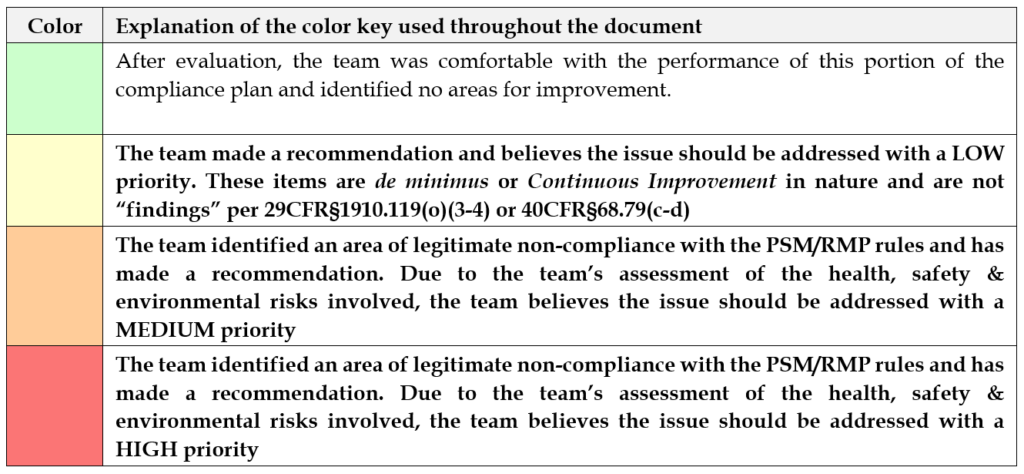

All right. Now you have collected all the deficiencies so you know the ground you need to cover to get where you want to be – or, in our analogy, how far it is to get out of the hole you are in. Now we need to figure out in what order we need address these issues. Hopefully, your audits have given you some guidance here. For example, this is the color code I use for my compliance audits:

Obviously in this scheme, we’d focus our efforts on the red items, then the orange, etc. You will want to prioritize the actions you take based on the risk to your employees, your community and your business. I strive to get the “buy-in” from the audit team during the audit itself so this step is pretty much done for you. However, you may have a lot of findings & recommendations to deal with so further prioritization can be useful.

Part 3: Formulate the plans & assign responsibility

Formulating the plan(s) is one of the most difficult parts of the whole endeavor: How do we address all the issues we’ve found? We’re going to use a few strategies to help us formulate our plan:

Grouping: One thing you may find is that a common root cause means you can group items. For example, if I have a poorly constructed MI inspection with 600 pipe label recommendations I can view each of those as individual recommendations or I can decide that the root cause is that we don’t have a system to ensure adequate pipe labeling. For me, I’d rather put a system in place to address that widespread deficiency than rely on just fixing the issues someone else found thus ensuring I’ll need them to find them next time too! For the example of pipe labeling, I would train my operating staff on the requirements of IIAR B114 and place a label check in the annual unit inspection work order. Properly implemented that system ensures that the issue will be addressed in the next year and will continue to be addressed regularly thereafter.

Don’t reinvent: There’s plenty of freely available templates for nearly all programs, procedures, work orders, etc. you may need. Don’t waste your time creating a policy or procedure from scratch when you can often use a pre-made one to address the issue with little or no change.

Don’t make Perfect the enemy of the Good: Sometimes altering a simple policy that solves the problem 99% of the time to one that solves it 100% of the time turns it into a lengthy and confusing mess. Policies and procedures aren’t meant to completely replace independent thought – they should be designed to guide it. We should bias our efforts towards “good enough” at first and strive towards perfection over time with continuous improvement.

Leverage Strengths & Avoid Weaknesses: Tasks should be assigned to people based on their competencies. For example, if you have a good core competency in your staff for writing SOPs, then by all means go ahead and write them. But if you don’t have anyone with that experience, maybe outsource that issue so their time is spent on the things they are already good at. Using a stock template and the needed PSI, my personal average for SOPs is about 1.5 hours. I’ve seen relatively competent people take 10 hours or more on the same SOP. The difference is that I wrote the template and have used it thousands of times. On the other hand, I’ve been known to take 3x as long as a skilled operator to change oil filters on a compressor because I’ve only done it a handful of times.

Assigning Responsibility is crucial. What we want is to have someone own the solution. Even if you assign a task to an outside consultant or contractor, make sure someone in-house is assigned the responsibility for the task to ensure they keep that 3rd party in-line and on-schedule.

Also keep in mind that this is a great place in this process to manage expectations. Often a facility has been neglecting their PSM duties for decades but seems shocked that the newly assigned PSM coordinator can’t solve the problem in a few weeks. Let’s just say that if it took 10 years to dig the hole, it’s not realistic to expect anyone to dig you out of it quickly.

Part 4: Implement, Implement, Implement!

Prussian military commander Helmuth van Moltke is famous for saying that “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” You are never going to get anywhere until you go out there and start implementing your plans. You can’t build a reputation on what you plan to do.

Don’t be hesitant to reassess and change the plan if things aren’t going well.

One of the most important things you can do during this part of the process is having regular PSM meetings. Make sure everyone assigned a task is asked about their progress. It may seem like a waste of time, but it’s also a good practice to go over the things you have already accomplished. I recommend this for two reasons:

As always, if there is anything we can do to help, please contact us!

Disclaimer: This post is a collaboration between an industry friend and colleague, Victor Dearman and I. The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the opinions of any entity whatsoever which we have been, are now, or will be affiliated.

It’s a question we hear often – sometimes as part of a PHA or Compliance Audit, but more often with someone just struggling to justify their staffing requests. Unfortunately, there really isn’t a simple, definitive answer to the question. No controlling RAGAGEP exists and state / local laws on the topic are relatively rare. This sort of problem isn’t rare in PSM because it is a performance-based standard. Our performance basis is that we are staffed sufficiently to ensure the safety of the people within the building and the surrounding community.

We need to answer the “How many Operators do we need?” question in a way that we can support it, or as we like to say, “Build a defensible case for the answer we arrive at. The answer itself will depend on many, many factors. So, let’s go on a journey and see how we can arrive at an answer we can feel confident in.

The road to an answer

The biggest factor for many is the design (age!?) of the system controls. A modern system with advanced controls requires less oversight on a day-to-day basis. If your system still relies on manual controls and people writing down pressures every hour, then that’s going to have a significant impact on your staffing needs. But once we get past that obvious issue, things get a bit more complicated.

Let’s be honest here, if things are running well; you have a good history with compliance audits, inspections, incident investigations, etc. and a low MI backlog, you’re probably not asking this question. If you are asking this question, it is probably due to an event related to a PSM/RMP element.

Let’s look at the kinds of element events that typically lead to this question.

Employee Participation: Look, everyone feels over-burdened at work, especially in the modern “Do MORE with LESS” era. But, if you pay attention to it, and look at these other elements, this employee feedback can provide valuable insights into the adequacy of your staffing.

Mechanical Integrity: What we’re looking for here is to understand if you have the skill sets and staffing to adequately maintain your refrigeration system. Whether you do everything in-house, or have a small in-house small crew performing basic rounds and contract out all the rest of the maintenance, inspections, and tests, is it adequate?

Here’s some MI related questions you might ask to help you determine if your staffing is adequate:

Incident Investigations: A review of incident investigation history can tell us a lot if the facility has a good process safety culture. But if they don’t have the right culture, and /or they don’t have any documented incidents, you’re going to have to do a little detective work and interview plant employees to find out if incidents are occurring that aren’t being recorded. Remember to spread your net wide here because incidents can happen at any time, not just on day-shift: Backshifts, weekends, holidays, etc. there’s no time immune to a possible incident.

You may also find indications of incidents occurring in walk-through logs, communications logs, ITPMRs, work orders, etc.

Here’s some II related questions you might ask to help you determine if your staffing is adequate:

Management of Change / Pre-Startup Safety Review: Properly implementing the MOC and PSSR elements takes a lot of time! We often find that these two elements are amongst the first to “fall behind” in suboptimal staffing situations. Here’s some MOC/PSSR related questions you might ask to help you determine if your staffing is adequate:

Process Hazard Analysis: The PHA and open PHA recommendations can also help us understand if our staffing levels are appropriate. There may also be indications in the PHA itself. There’s a portion of the PHA that deals with staffing directly, but we’ll deal with that in the Building a defensible case on staffing section of this article.

Here’s some PHA related questions you might ask to help you determine if your staffing is adequate:

Emergency Action and Response Plans: Whether we’re looking at the plan(s) themselves, or analyzing an after-action report, a there can be a lot to learn here concerning proper staffing levels. Obviously, the required staffing levels for Emergency Response facilities is going to be higher, but that doesn’t mean there is no staffing requirement for Emergency Action plans.

Here’s some EAP/ERP related questions you might ask to help you determine if your staffing is adequate:

Building a defensible case on staffing

Ok, we’ve answered our questions and gathered a good impression of where we stand – and where we should stand. Maybe we need to adjust our staffing levels and/or increase the amount of services we ask contractors to complete for us. Where should we document this? In our opinion, the place in the system where the facility already had the opportunity to address this issue, was in the PHA. So, let’s go back to the PHA, end see if our results match the PHA team’s.

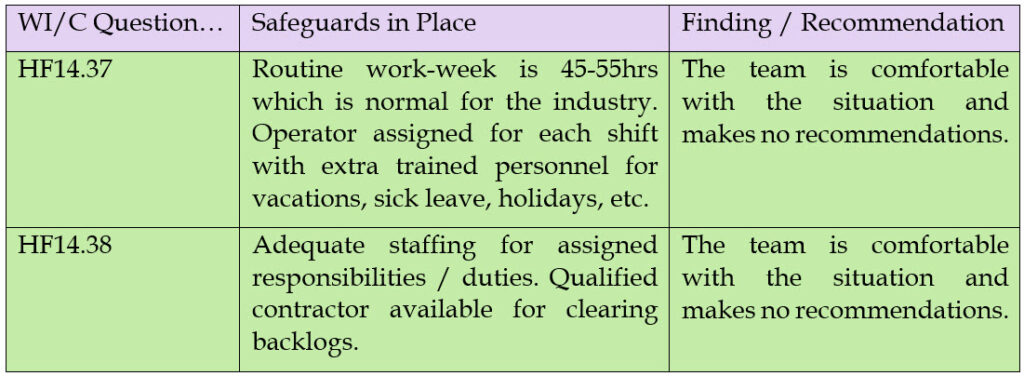

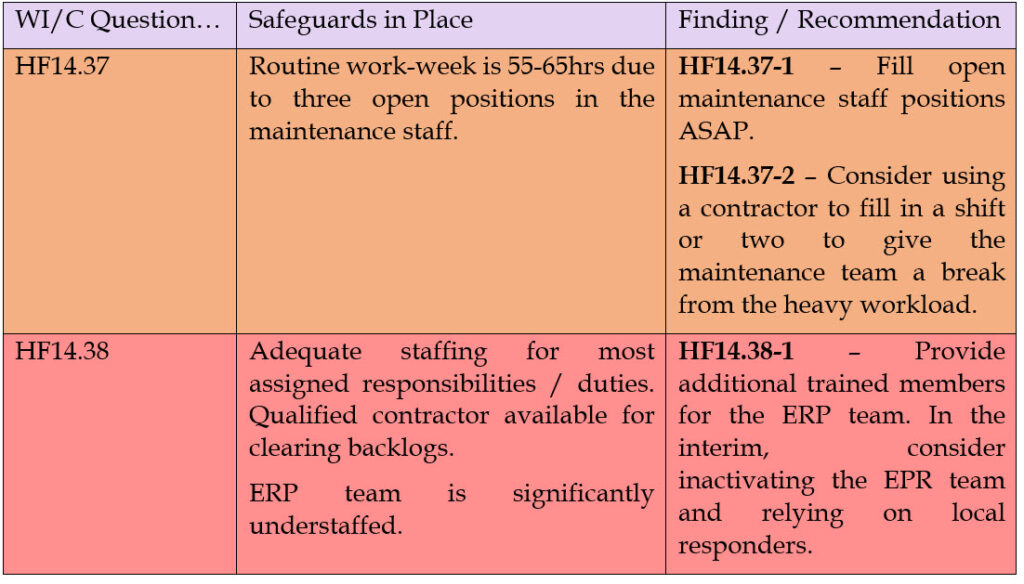

You are going to be looking for the following two questions (or their equivalents) from the standard Human Factors section of the IIAR What-If /Checklist worksheets:

HF14.37 – What if an employee is stressed due to shift work and overtime schedules?

HF14.38 – What if there are not sufficient employees to properly operate the system and respond to system upsets?

During the PHA, the facility should have answered those in a way that says they have adequate staffing or recommended that staffing be increased. Let’s say you decided that you had adequate staffing based on your answers to the questions above. If that’s the case, we’d expect to see something like the following:

If, however, we found some areas for improvement, we might expect something like this:

Closing Thoughts: We hope you didn’t start reading this hoping for an easy answer, but we’re fairly certain – now that you understand the full scope of the question being asked – that the answer doesn’t need to be easy, it needs to be correct and defensible.

You can build a much better understanding of your staffing needs by looking at the existing elements in your Process Safety program. Any decent Compliance Audit would cover this same ground, if staffing is an area of concern for you, make sure to bring it up.

—

P.S. from Victor: Some facilities might try and get more value from a security guard on off shifts or holiday coverage to make roving patrols and report abnormal conditions and alarms? Sure, but that also means that guard has to be trained to identify what the alarms mean, how to identify an abnormal condition, and that they know what to do to either immediately correct the deviation or immediately contact someone that can (on call techs or service providers). By the time you have invested this much into a guard, you could have paid for a well-qualified operator.

My advice to any organization when making these decisions is to evaluate the above and take into consideration the attracting well rounded operators with the skill sets and experience often sought is more often through word of mouth about how the organization projects their Process Safety culture.

How to hire operators? Well, that sounds like a good subject for a future article!

The Issue: Recently an industry friend reached out with a question that I thought was worth sharing. They recently had some fierce storms roll through their area that involved tennis-ball sized hail. This hail caused some insulation damage, but didn’t cause any ammonia release. Here are some pictures of the type of damage they experienced.

Hail Damage pictures

The question is “Would this require an Incident Investigation?”

The Law: As always, first we look at the law.

OSHA 29CFR1910.119(m)(1): The employer shall investigate each incident which resulted in, or could reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release of highly hazardous chemical in the workplace.

EPA 40CFR68.81: The owner or operator shall investigate each incident which resulted in, or could reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release.

While there is obvious damage to the protective jacketing and vapor barrier, you could make a defensible argument that this is not something that could “reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release of highly hazardous chemical.” That’s not to say there isn’t any value to such an investigation, but that there most likely is not a requirement to investigate this incident based solely on the PSM/RMP rules. But, the rules aren’t the only guidance available to us, so let’s look further.

RAGAGEP and Written Programs: In my opinion, the best RAGAGEP available on the topic is the CCPS book Guidelines for Investigating Chemical Process Incidents, 2nd Edition, which is what inspired the approach we take in our Incident Investigation element Written Plan. Similarly, the IIAR’s publication PSM & RMP Guidelines makes roughly the same types of arguments and include an EPA suggestion that any damage of $50,000 or more should be investigated. If you’ve priced insulation recently, you know we’re likely to hit that threshold.

Here’s the relevant part of our Incident Investigation element Written Plan which incorporates the CCPS guidance:

An Incident is an unusual or unexpected occurrence, which either resulted in, or had the potential to result in:

- Serious injury to personnel

- Significant damage to property

- Adverse environmental impacts

- A major disruption of process operations

That definition implies three types or levels of incidents:

Accident – An occurrence where property damage, material loss, detrimental environmental impact or human injury occurs. (off-site Ammonia release, product in freezer exposed to ammonia, personnel injury, etc.)

Near Miss – An occurrence when an accident could have happened if the circumstances were slightly different. We sometimes call these incidents “An Accident where something went right”. (Forklift strikes an air unit causing only cosmetic damage and no Ammonia is released, an activation of an automatic shutdown, etc.)

Process Upset / Interruption – An occurrence where the process was interrupted. (Vessel high-level alarm, a nuisance ammonia odor report, ice buildup on an air unit preventing it from cooling properly, failing to conduct required PSM activities as scheduled, etc. Many Process Interruptions are fixed before the event leads to a shutdown. If the equipment was shut down manually or automatically in response to an unexpected occurrence, then the incident is to be investigated as a Near Miss.

This storm damage would seem to trigger the “Significant damage to property” part of the Incident definition and classify it as an Accident due to “property damage.” In accordance with the relevant RAGAGEP and our element Written Plan, we’d expect you to conduct an Incident Investigation despite a defensible argument that the PSM/RMP rules do not require one.

What we accomplish with an Incident Investigation: With a formal assessment of the incident, we’re hoping to document the following:

Conclusion: While it seems pretty clear the PSM/RMP rules themselves wouldn’t require an Incident Investigation, RAGAGEP would and there’s much to be gained from one.

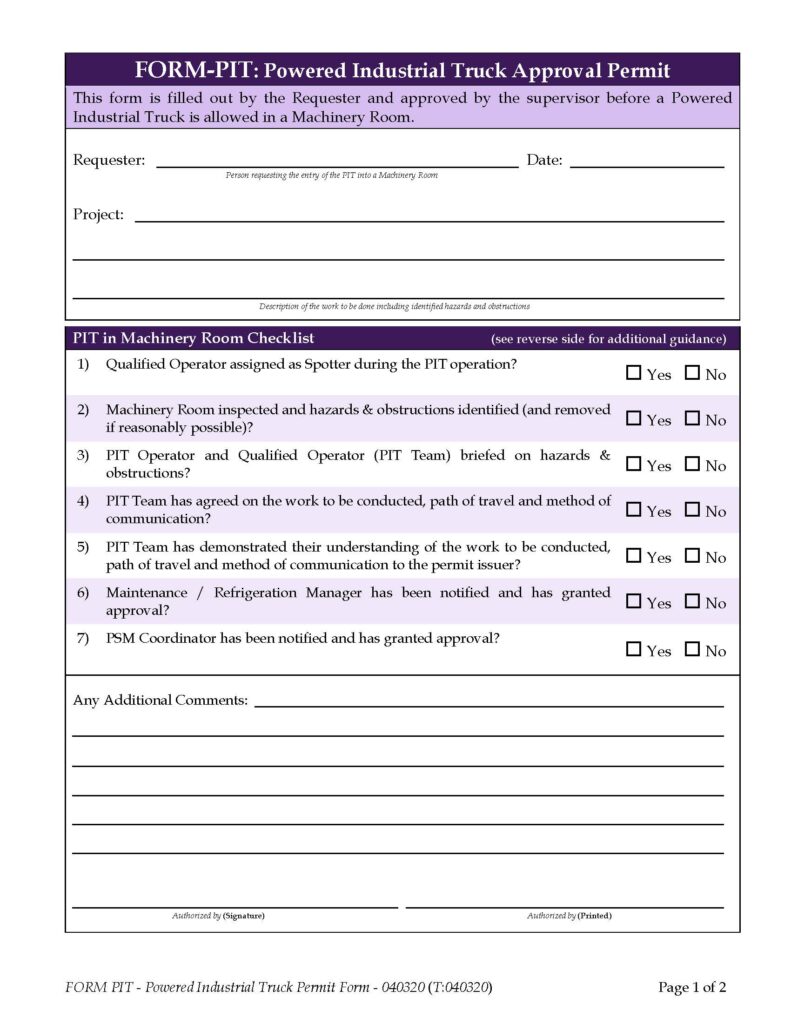

Powered Industrial Trucks (PIT) in Machine Rooms are a known struck-by hazard. What most people don’t realize is how serious the results of a PIT impact in a Machinery Room can be.

For example, a forklift / scissor lift impact that shears a 3″ TSS (ThermoSyphon Supply) or HPL (High Pressure Liquid) operating at a typical head pressure of 160PSIG results in a release rate of over 18,500 pounds per minute.

Many facilities attempt to establish a ban on PIT in their machinery rooms, but while the needs for PIT in machine rooms are very limited, there are situations where they are necessary. An outright ban won’t likely survive prolonged contact with reality.

To address this issue in a PHA, we usually recommend a Written Machine Room PIT policy as an administrative control. For years we’ve discussed the content of that policy informally with people. Recently a PSM coordinator shared her written policy & permit with us and after some alterations and formatting, we’re adding it to the SOP Templates section.

Front of the Permit:

Back of the Permit with additional explanations:

As always, you can find this on the Google Shared template drive.

The whole country is facing a very difficult situation right now as we all deal with both the COVID-19 disease and the effects of government’s response to it. Some customers (especially restaurant service) are seeing a 2/3rds drop in their business. Other sectors, such as Grocery, are seeing unprecedented demand. Either way, that’s a recipe for chaos.

One of the first cultural victims of chaos is usually the safety / regulatory community. We’re easy to ignore whether the reason is “we’re facing layoffs and bankruptcy” or “orders are up 300% and we don’t have time for this.”

On top of that, in a good-faith effort to re-assure the regulated community that they understand the burdens we’re under right now, the EPA drafted a policy saying they would use discretion on compliance during the pandemic.

That EPA policy was interpreted by some (the environmental lobby mostly) as a blanket waiver of all regulations allowing the regulated community to pollute at will. More significantly worrying to me personally was the calls, emails & texts I started getting Friday where people in our refrigeration community were being “told” this temporary EPA policy was being used to avoid compliance with their PSM / RMP obligations.

With that in mind, let’s look at what it actually says, shall we?

What is the EPA actually saying?

Here’s the actual EPA press release. Here’s the actual EPA guidance memorandum. Here’s the important part:

- Entities should make every effort to comply with their environmental compliance obligations.

- If compliance is not reasonably practicable, facilities with environmental compliance obligations should:

- Act responsibly under the circumstances in order to minimize the effects and duration of any noncompliance caused by COVID-19;

- Identify the specific nature and dates of the noncompliance;

- Identify how COVID-19 was the cause of the noncompliance, and the decisions and actions taken in response, including best efforts to comply and steps taken to come into compliance at the earliest opportunity;

- Return to compliance as soon as possible; and

- Document the information, action, or condition specified in a. through d

The consequences of the pandemic may constrain the ability of regulated entities to perform routine compliance monitoring, integrity testing, sampling, laboratory analysis, training, and reporting or certification. … In general, the EPA does not expect to seek penalties for violations of routine compliance monitoring, integrity testing, sampling, laboratory analysis, training, and reporting or certification obligations in situations where the EPA agrees that COVID-19 was the cause of the noncompliance and the entity provides supporting documentation to the EPA upon request.

What does that mean for us in PSM/RMP covered processes?

Short answer: Not a lot. Long answer follows…

Here’s some examples of what it might let you avoid a fine for:

Here’s some examples of what it definitely WILL NOT let you avoid a fine for:

Accidental Releases: Nothing in this temporary policy relieves any entity from the responsibility to prevent, respond to, or report accidental releases of oil, hazardous substances, hazardous chemicals, hazardous waste, and other pollutants, as required by federal law, or should be read as a willingness to exercise enforcement discretion in the wake of such a release.

Closing thoughts

Unless you are in a very unique position, this EPA memo means very little to you at all. Here’s examples of two clients that it does affect: