Let us help you make sense of PSM / RMP!

We’ll be having an open-enrollment PSM class in Burleson, Texas July 8th-11th 2025.

You can get more information on the class with this link.

We hope to see you there!

Chill - We Got This!

Let us help you make sense of PSM / RMP!

We’ll be having an open-enrollment PSM class in Burleson, Texas July 8th-11th 2025.

You can get more information on the class with this link.

We hope to see you there!

The issue: A facility with an ammonia refrigeration system notes that their HPR level is rather low, and they are considering ordering some ammonia to get back to the levels they “used to have.” The thinking is that they need to add to the ammonia charge to make up for ammonia that was lost over the years.

Before you go too far, a good question to ask is: Did I lose ammonia? Or is it just somewhere else in my system?

What if you didn’t lose it?

Did you add equipment without your MOC addressing if this required an inventory adjustment? Did you change recirculator vessel levels which make the HPR look low even though the ammonia is still out in the system? Has someone been mucking with the HXV’s or TXV’s, so you are “brining” coils? These are common issues, but the most likely culprit is seasonal variation.

If it’s August in Texas, it’s likely that your system is running about as hard as it will ever run. That means that the NH3 isn’t just hanging out in your vessels, but out in the various heat exchangers (and their piping) doing its job. The “good old boy” method of testing this was to wait until the cool of the night, shut down the liquid feed to your “load,” and check the vessel levels after the NH3 came back.

A more “modern” method is to use an inventory spreadsheet and adjust the levels in the heat exchangers to reflect the summer load. The intricacies of doing either of these are better dealt with in the real world rather than a blog-post, so let’s assume you have already checked this and you actually do need ammonia. (Note: if you need assistance with either of the above, we can certainly assist you, just give us a call)

Ok, maybe we did lose it!

If you look into the situation and find out that you actually do need ammonia, there are a few considerations you should think of BEFORE you order that truck and start preparing for delivery.

Justifying the charge

Assuming you didn’t have some sort of incident that clearly explains why you need ammonia, we should figure out how to justify the amount we’re adding. Most losses are easily justified by establishing a “loss rate” and comparing it to accepted norms. This acceptable loss would be caused by normal maintenance, auto-purgers, and fugitive emissions.

In my opinion, anything less than 5% is good. 2-3% is excellent. For what it’s worth, the IIAR has stated that up to 10% loss a year is “reasonable.”

A loss rate of 3% or less a year can easily be explained from normal maintenance, auto-purgers, and fugitive emissions.

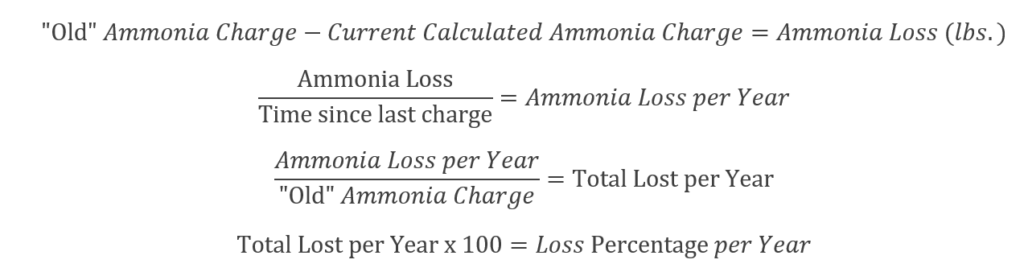

This is easier to explain with a worked example from a friend. In this case, their inventory level is supposed to be 5,800lbs. When they updated their inventory sheet to reflect the actual conditions at the facility, they saw a calculated current charge of 5,000lbs reflecting an 800 pound loss. That loss occurred since their last charge 5 years ago.

This percentage is easily explainable from maintenance and other fugitive emissions, and it’s also quite reasonable.

If you take the time to figure out the math above, and then document your calculations to justify your NH3 charge, it helps avoid unpleasant assumptions on the part of the EPA and OSHA in any future inspections.

If an auditor comes in and sees an ammonia delivery receipt, a documented rationale why the ammonia was needed, the SDS of the chemical charged, and you have a compliant charging procedure, it would be very unlikely that the charging process would be questioned further.

Of course, if your math shows a high leak rate, then you had better get an incident investigation going and figure out what’s wrong!

P.S. – To assist in this effort, Scott updated the Ammonia Inventory example template has been updated to help automate this process. Just enter the old value, newly measured value, and time (in months) since last charging and you have a 1-page report on the % loss per year. We hope this helps. The file can be located at: \ PSM-RMP Program Templates \ 03 – Process Safety Information \ Optional Resources \

“Smart people learn from their mistakes. Wise people learn from the mistakes of others.”

Or, in PSM terms: Incident Investigation is how you become smart. Process Hazard Analysis is how you become wise.

Yesterday, a horrific explosion occurred in the port of Beirut, Lebanon. This morning it is being reporting that over 100 are dead, over 4,000 are injured, and up to 300,000 are homeless. Estimates of the economic damage have been as high as five billion dollars.

Beirut, Lebanon Explosion 08/04/20

It is believed that the explosion was the result of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate stored at the port. The authorities will now have to try and piece together what happened to see what they can learn from this incident.

Beirut, Lebanon Explosion Aftermath 08/04/20

In PSM terms, this is where we implement the Incident Investigation element. Refer back to that earlier quote, “Incident Investigation is how you become smart.” One of my first mentors put it another way: “Wisdom is healed pain.” It is right and proper that we learn from the mistakes we make, but there is a better way: Learn from the mistakes of others so you don’t repeat them!

Al Jazeera is reporting that the chemical storage was known about for seven years, and while the port authorities asked for assistance in dealing with the dangerous situation SIX TIMES, they did not receive a response. It appears that the authorities in Beirut had the information they needed to KNOW they had a hazards to address for many years.

The dangers of Ammonium Nitrate explosion are WELL KNOWN. Check out this older article on the events in West, Texas – or check out the pictures I took there after the explosion. (Note, according to the Al Jazeera timeline, the improper storage of this chemical in Lebanon began right around the time of this incident in America.)

Ammonia Nitrate explosion damage in West, Texas (2013)

A proper PHA prevents incidents. In the PHA process, we Identify hazards, Evaluate those hazards, and then Control those hazards.

A timely Process Hazard Analysis would have shown OBVIOUS problems with Facility Siting, RAGAGEP compliance, and equipment / facility suitability. It appears that in Beirut, the port officials informally identified at least some of the hazards, and to some degree they analyzed them. Those responsible in Beirut had AMPLE opportunity to CONTROL the hazards but chose not to – for reasons we don’t yet know.

Put another way, because they did not accept their responsibility to perform a Process Hazard Analysis, they now have to accept their somber duty to perform an Incident Investigation.

Incident Investigation is how you become smart. Process Hazard Analysis is how you become wise.

Are there any issues in your facility that you are aware of that you haven’t yet addressed? Consider this tragedy in Beirut as a reminder to take action on them. There’s no time like the present!

P.S. There are large Ammonia Nitrate stockpiles all over the world. When stored properly it is very, very safe. But storing it next to a fireworks warehouse in a vault that wasn’t designed for it is begging for a disaster.

— Update: The Times of Israel quotes Lebanese Prime Minister Hassan Diab as saying: “What happened today will not pass without accountability. Those responsible for this catastrophe will pay the price.” With respect, no, they won’t pay the price.

The people that died paid the price. The loved ones of the deceased, the people that were injured, and those who are now homeless are paying the price. The people responsible may pay a price, but it’s unlikely to be as severe as the one paid by those who had no part in the series of errors that lead to this catastrophe.

The Issue: Recently an industry friend reached out with a question that I thought was worth sharing. They recently had some fierce storms roll through their area that involved tennis-ball sized hail. This hail caused some insulation damage, but didn’t cause any ammonia release. Here are some pictures of the type of damage they experienced.

Hail Damage pictures

The question is “Would this require an Incident Investigation?”

The Law: As always, first we look at the law.

OSHA 29CFR1910.119(m)(1): The employer shall investigate each incident which resulted in, or could reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release of highly hazardous chemical in the workplace.

EPA 40CFR68.81: The owner or operator shall investigate each incident which resulted in, or could reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release.

While there is obvious damage to the protective jacketing and vapor barrier, you could make a defensible argument that this is not something that could “reasonably have resulted in a catastrophic release of highly hazardous chemical.” That’s not to say there isn’t any value to such an investigation, but that there most likely is not a requirement to investigate this incident based solely on the PSM/RMP rules. But, the rules aren’t the only guidance available to us, so let’s look further.

RAGAGEP and Written Programs: In my opinion, the best RAGAGEP available on the topic is the CCPS book Guidelines for Investigating Chemical Process Incidents, 2nd Edition, which is what inspired the approach we take in our Incident Investigation element Written Plan. Similarly, the IIAR’s publication PSM & RMP Guidelines makes roughly the same types of arguments and include an EPA suggestion that any damage of $50,000 or more should be investigated. If you’ve priced insulation recently, you know we’re likely to hit that threshold.

Here’s the relevant part of our Incident Investigation element Written Plan which incorporates the CCPS guidance:

An Incident is an unusual or unexpected occurrence, which either resulted in, or had the potential to result in:

- Serious injury to personnel

- Significant damage to property

- Adverse environmental impacts

- A major disruption of process operations

That definition implies three types or levels of incidents:

Accident – An occurrence where property damage, material loss, detrimental environmental impact or human injury occurs. (off-site Ammonia release, product in freezer exposed to ammonia, personnel injury, etc.)

Near Miss – An occurrence when an accident could have happened if the circumstances were slightly different. We sometimes call these incidents “An Accident where something went right”. (Forklift strikes an air unit causing only cosmetic damage and no Ammonia is released, an activation of an automatic shutdown, etc.)

Process Upset / Interruption – An occurrence where the process was interrupted. (Vessel high-level alarm, a nuisance ammonia odor report, ice buildup on an air unit preventing it from cooling properly, failing to conduct required PSM activities as scheduled, etc. Many Process Interruptions are fixed before the event leads to a shutdown. If the equipment was shut down manually or automatically in response to an unexpected occurrence, then the incident is to be investigated as a Near Miss.

This storm damage would seem to trigger the “Significant damage to property” part of the Incident definition and classify it as an Accident due to “property damage.” In accordance with the relevant RAGAGEP and our element Written Plan, we’d expect you to conduct an Incident Investigation despite a defensible argument that the PSM/RMP rules do not require one.

What we accomplish with an Incident Investigation: With a formal assessment of the incident, we’re hoping to document the following:

Conclusion: While it seems pretty clear the PSM/RMP rules themselves wouldn’t require an Incident Investigation, RAGAGEP would and there’s much to be gained from one.

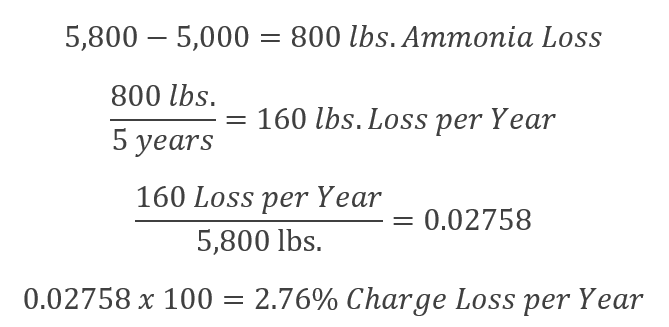

Powered Industrial Trucks (PIT) in Machine Rooms are a known struck-by hazard. What most people don’t realize is how serious the results of a PIT impact in a Machinery Room can be.

For example, a forklift / scissor lift impact that shears a 3″ TSS (ThermoSyphon Supply) or HPL (High Pressure Liquid) operating at a typical head pressure of 160PSIG results in a release rate of over 18,500 pounds per minute.

Many facilities attempt to establish a ban on PIT in their machinery rooms, but while the needs for PIT in machine rooms are very limited, there are situations where they are necessary. An outright ban won’t likely survive prolonged contact with reality.

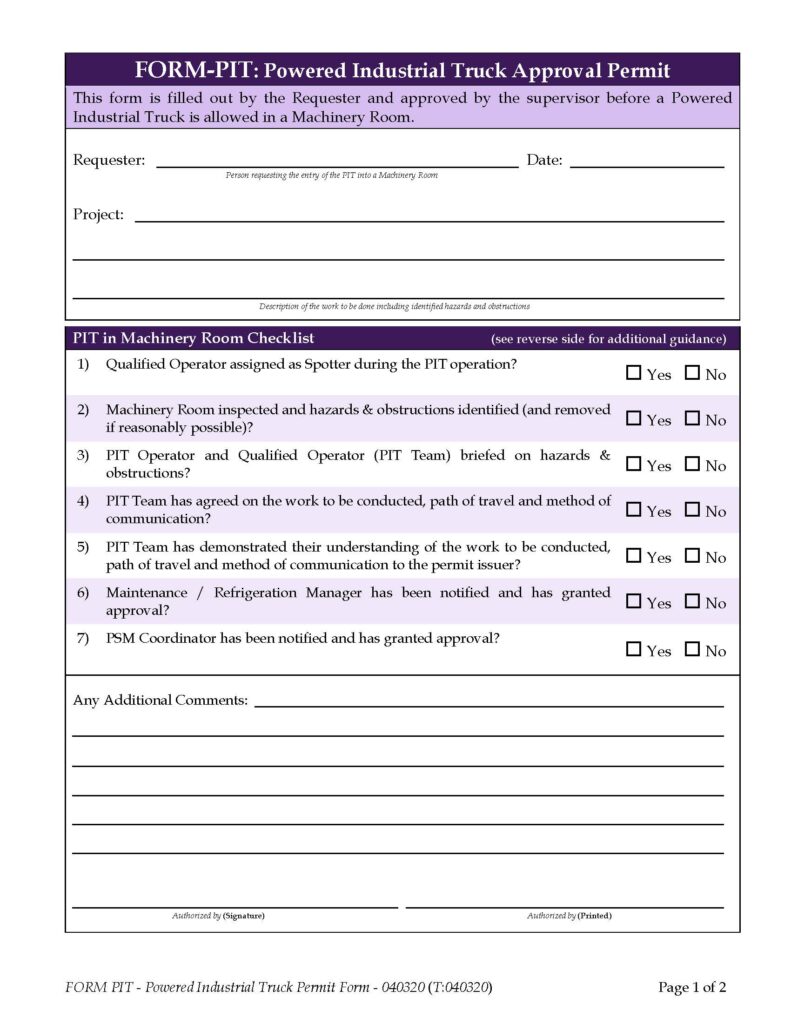

To address this issue in a PHA, we usually recommend a Written Machine Room PIT policy as an administrative control. For years we’ve discussed the content of that policy informally with people. Recently a PSM coordinator shared her written policy & permit with us and after some alterations and formatting, we’re adding it to the SOP Templates section.

Front of the Permit:

Back of the Permit with additional explanations:

As always, you can find this on the Google Shared template drive.

“U.S. Chemical Safety Board and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) has approved a final rule on accidental release reporting. The CSB has posted a prepublication version of the final rule… The official version should be published early next week in the Federal Register.

The rule requires prompt reports to the CSB from owners or operators of facilities that experience an accidental release of a regulated substance or extremely hazardous that results in a death, serious injury or substantial property damage. The CSB anticipates that these reports will provide the agency with key information important to the CSB in making prompt deployment decisions…

The rule is required by the CSB’s enabling legislation but was not issued during the first 20 years of CSB operations. Last year, a court ordered the CSB to finalize a rule within a year. “

What it means: If the incident resulted in Death, Serious Injury or Substantial Property Damage ($1kk or more) then you have to report the incident to the CSB (via phone 202- 261-7600 or email report@csb.gov) within 30 minutes. The report must include:

1604.4 Information required in an accidental release report submitted to the CSB

1604.4 The report required under §1604.3(c) must include the following information regarding an accidental release as applicable:

1604.4(a) The name of, and contact information for, the owner/operator;

1604.4(b) The name of, and contact information for, the person making the report;

1604.4(c) The location information and facility identifier;

1604.4(d) The approximate time of the accidental release;

1604.4(e) A brief description of the accidental release;

1604.4(f) An indication whether one or more of the following has occurred: (1) fire; (2) explosion; (3) death; (4) serious injury; or (5) property damage.

1604.4(g) The name of the material(s) involved in the accidental release, the Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) number(s), or other appropriate identifiers;

1604.4(h) If known, the amount of the release;

1604.4(i) If known, the number of fatalities;

1604.4(j) If known, the number of serious injuries;

1604.4(k) Estimated property damage at or outside the stationary source;

1604.4(l) Whether the accidental release has resulted in an evacuation order impacting members of the general public and others, and, if known:

1604.4(l)(1) the number of persons evacuated;

1604.4(l)(2) approximate radius of the evacuation zone;

1604.4(l)(3) the type of person subject to the evacuation order (i.e., employees, members of the general public, or both).

The good news is that if you have to report the incident to the NRC then you can skip reporting all the above data and simply report the NRC case number you’re given during the NRC call.

This new requirement takes effect 30 days from the posting in the Federal Register so ACT NOW. It’s important that you update your program because there are enforcement penalties associated with not following this new rule…

1604.5(b) Violation of this part is subject to enforcement pursuant to the authorities of 42 U.S.C. 7413 and 42 U.S.C. 7414, which may include

1604.5(b)(1) Administrative penalties;

1604.5(b)(2) Civil action; or

1604.5(b)(3) Criminal action.

What should I do?

If you use the template program, the hard work has already been done FOR YOU. Just open up the template directory on Google Drive and follow these steps for your program:

Note: If you have instructions for Agency Notifications somewhere outside your Incident Investigation plan, you’ll need to update them to include the CSB contact information there too. Feel free to use the text in the Incident Investigation element Written Plan, Implementation Policy: Agency Notifications.

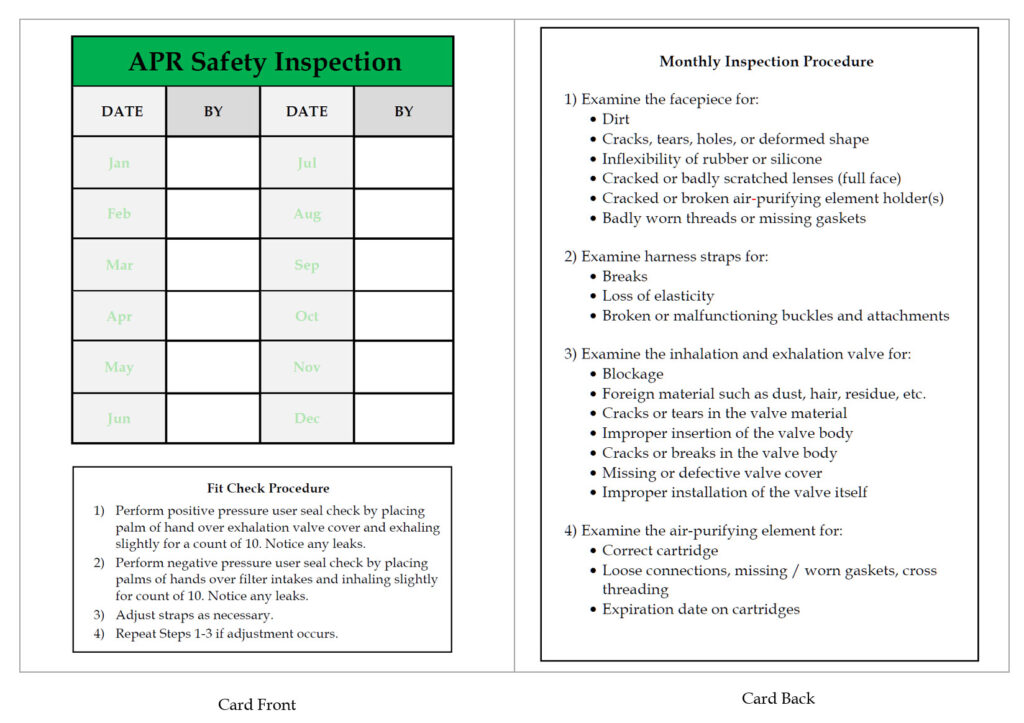

Sometimes a little extra can go a long way to improve the effectiveness of your compliance efforts. I would like to show you how we used two simple, inexpensive laminated cards to improve the effectiveness of our APR inspections and Incident reporting / reactions.

APR Card

First, the APR issue:1910.134 has some requirements on inspections, cleaning, fit-check, etc. We require our service technicians to wear APR’s during Line-Opening. I created a small laminated card (about 5″x8″) that fits in their APR bag. With the included permanent marker, we can track the APR inspections for a year. The card also provides convenient information on the “Fit-Check” and “Monthly Inspection” procedures. Here’s the WORD document if you want to modify it for your use.

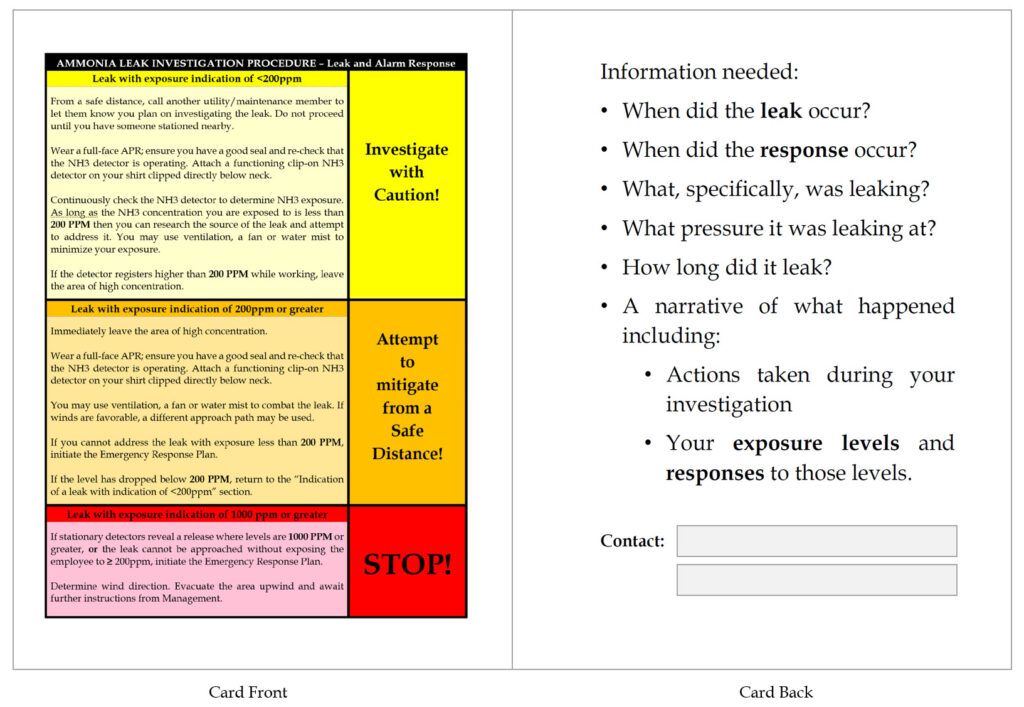

Leak Investigation / Incident Reporting

Our technicians are often called to look into reported ammonia odors. We’ve established a policy on doing this in compliance with 1910.119(n) concerning “handling small releases.” We also conduct Incident Investigations to meet the requirements of 1910.119(m). Again, I created a small laminated card (about 5″x8″) that fits in their APR bag. It provides a quick-reference to the investigation procedure, as well as reminders of the information we’ll be asking them for. Contact numbers for company safety/compliance resources are also included. Here’s the WORD document if you want to modify it for your use.

Little items like this can reinforce your training. The easier “being compliant” is, the more likely it is to happen in the field!

p.s. The Word documents are meant to be printed double-sided. I use 32# paper, trim, then seal with 5mil clear laminating envelopes.

Most LEO (Line & Equipment Opening) policy a.k.a. “Line Break” policies require a second person away from the work but in the immediate area. It is reasonable to ask why the procedure demands this.

Put as simply as possible:

Let’s work through this step-by-step

1. PSM/RMP requires us to have a procedure:

1910.119(f)(4) The employer shall develop and implement safe work practices to provide for the control of hazards during operations such as lockout/tagout; confined space entry; opening process equipment or piping; and control over entrance into a facility by maintenance, contractor, laboratory, or other support personnel. These safe work practices shall apply to employees and contractor employees.

Put another way: We have to develop a written procedure on Line & Equipment Openings which everyone must follow.

2. Hazards identified during a PHA are often controlled with Administrative controls, such as SOPs. SOP content therefore must address the hazards identified in the PHA. Some examples:

…the Ammonia exposure increases while the operator is using an APR/SCBA? (II.8) This is what makes us mandate the use of a personal NH3 detector during line openings and leak investigations.

…there is inadequate isolation prior to maintenance? (HF.3) …the Ammonia pump-out for a length of piping or for a piece of equipment is incomplete? (PO.1) This is why SOPs include a pressure check to confirm pumpdown. This is also why the LEO procedure (and permit) require a written SOP & permit to check the effectiveness of the procedure.

…an injured worker is unable to summon assistance? (HF.56) This (among other reasons) is why we require a Buddy System. The LEO policy, in the General Precautions section, states “A buddy-system is used for all LEO procedures. The second person must be trained to initiate emergency action and must be stationed close enough to observe the activity but far enough away to ensure that they would not be endangered by an accidental release.”

3. The RAGAGEP for procedures IIAR 7-2019 has this requirement:

4.4.2 Buddy System. Operating procedures shall indicate when the buddy system shall be practiced in performing work on the ammonia refrigeration system

A4.4.2-The buddy system should be practiced for operations where there is the potential that ammonia could be released, for example, operations which involve opening ammonia refrigeration equipment or piping. The buddy system should also be practiced during emergency operations involving ammonia releases.

4. HazMat & Firefighting history: Hazardous Materials teams and Firefighters have long used a 2-person team for increased safety. To some degree, this is enshrined in OSHA rules in 1910.134(g)(3)…

1910.134(g)(3) Procedures for IDLH atmospheres. For all IDLH atmospheres, the employer shall ensure that:

1910.134(g)(3)(i) One employee or, when needed, more than one employee is located outside the IDLH atmosphere;

1910.134(g)(3)(ii) Visual, voice, or signal line communication is maintained between the employee(s) in the IDLH atmosphere and the employee(s) located outside the IDLH atmosphere;

While we don’t INTEND to work inside a IDLH atmosphere during a LEO procedure, the possibility certainly exists if something goes wrong. The “buddy system” allows the person performing the LEO to focus on the work while the second person remains in the area situationally aware and ready to respond in the event that the situation changes or something goes wrong.

5. Human Nature: The LEO policy is written around accountability. The policy requires that we demonstrate to a second person that we’ve followed the policy and adequately prepared for the work before the LEO occurs. The “buddy system” tends to keep the actions “in-line” during the actual work.

Note: While it’s certainly possible – from a regulatory view – that you could have certain specific LEO procedures that did not require a “buddy,” you would have to be able to document how you managed to address all of the issues outlined above without the second person.

Thanks to Bryan Haywood of SaftEng.net and Gary Smith of ASTI (Ammonia Safety Training Institute) for their time and thoughts in helping review this post.

The view that PSM is a time-sink.

A common push-back from facilities that are covered under the OSHA PSM and EPA RMP regulations is the sheer amount of resources these programs require to successfully design, implement, and maintain.

One phrase, seared into my memory, is from a frustrated and over-burdened maintenance manager: “PSM is a thief!”

He was referring to the fact that he had to task high-performing, highly trained and highly compensated personnel to perform Process Safety tasks. Time spent on Process Safety is obviously time that isn’t spent elsewhere.

My counterpoint at the time was “Safety isn’t earned – it is rented. And the rent is due every damned day”

After an experience I had last week, I think there’s a better way to respond. I’d like to share my new response with you, but first let’s talk about the experience that made me see a new way of approaching this issue.

The experience

During the recent RETA conference the guest speaker was Jóse Matta. Jóse suffered ammonia burns over 40+ percent of his body when a condenser failed in an overpressure event. The event involved a portable ammonia refrigeration system. Before transport the system is drained of ammonia. In this incident, the driver placed a cap on the relief valve outlet due to DOT concerns. However, once the unit arrived onsite, the capped relief valve wasn’t noticed. Eventually this led to an overpressure event once the unit was charged and started.

Jose Matta barely survived his exposure. He nearly died in the hospital. His wife was brought into the burn unit to say her final goodbyes to her husband – the father of their children. When he was lucky enough to survive, he had to endure multiple surgeries. He no longer has a sense of smell and can barely taste food. He no longer has the ability to sweat and has to constantly monitor his condition when it’s hot out to avoid heat-stress or heat-stroke.

What does Jose’s experience have to do with “PSM as a thief?”

Post-incident, several failures of the PSM program were noted:

If the Process Safety items above were properly in place, the incident either wouldn’t have happened, or the outcome would have been significantly better for Jóse.

You see, when I pushed back from the “PSM is a Thief” argument before, I was wrong. I should have agreed with that statement.

PSM *is* a thief. Yes, it takes resources, but it can also take a LOT more from you!

PSM can steal from you: the opportunity to nearly die in a chemical release.

PSM can steal from your family: the opportunity for tearful goodbyes.

PSM can steal from you: years of surgeries, painful rehabilitation, and diminished health.

Yeah, PSM is a thief. I’m plenty happy to have these experiences stolen from me and the people I work with.

Without Process Safety, people are taking risks without knowing they are taking them. NOBODY should have to do that.

If you want your Process Safety program to steal these experiences from your facility, your coworkers, your neighbors, and YOU, we can help!

The issue: Poor Incident Investigations and how to improve them

Often members of the Incident Investigation team miss some fairly obvious opportunities to improve their process safety. One trick is to use the Hierarchy of Controls as a brainstorming tool when coming up with causes and recommendations.

What is the Hierarchy of Controls and How can I use it as a tool during Incident Investigations?

The premise of the Hierarchy of Controls is that while hazards can be controlled in various ways, certain types of controls are inherently better than others. The hazard controls in the hierarchy are, in order of decreasing effectiveness:

![]()

Let’s take an example of an Incident Investigation concerning an unexpected employee NH3 exposure during an oil drain. While you will have to address any unique issues relating to the incident, here are some questions that the Hierarchy of Controls can provide for any oil drain incident:

Elimination: Physically removing the hazard. For example, when analyzing the risk of a valve packing leak in a process room, moving that valve to the roof would eliminate the hazard from the production room. Elimination is usually considered the most effective hazard control.

Substitution: Replacing the hazard with something that does not produce a hazard or something that produces a much smaller hazard. A common example of this is removing the hazard of NH3 in product chillers areas with the use of a secondary refrigerant such as CO2 or Glycol. Note that in some instances this results in simply relocating a hazard to another area with lesser consequences.

Note: We usually combine these two methods because if we don’t, we tend to spend more time arguing whether or not a control is an elimination or a substitution.

Engineering Controls: These controls do not eliminate hazards but tend to attempt to control them or give notice when the process is approaching an unsafe state. Examples include NH3 sensors, Interlocks, High-Level Floats, Pressure and Temperature transducers, etc.

Administrative Controls: These controls are changes in the way the work is performed on or around the process. Training, Procedures, Signs and Warning labels are all administrative controls.

Personal Protective Equipment: PPE such as gloves, respirators, etc. is generally considered the last resort of hazard control.

Using the Hierarchy of Controls can be a great brainstorming tool to help you look at your possible causes, and your possible corrections from some new angles.