A friend in the industry recently went through an OSHA ChemNEP inspection on their NH3 Refrigeration System. Over the years, I’ve had the pleasure of working with many of their team members and have audited several of their facilities. They use an older version of the PSM/RM Program templates that I currently offer. They were kind enough to provide the (paraphrased) Dynamic List questions they were asked by the inspector.

What follows are those questions and my thoughts on how those questions are addressed in the current templates. Furthermore, there are often some additional questions you can ask to ensure you can document compliance with the PSM/RMP rules if you are asked these questions.

Black text concerns the question that was asked. Colored text are my thoughts on the responses for people that use the templates I provide.

Primary / Generic Question Pool

Do EAP procedures include small and large release plan?

This is a difficult one to answer as we don’t include the Emergency Action Plan (which could include evacuations due to Bomb Threats, Terrorism, Fires, Earthquakes, Floods, etc.) or Emergency Response Plan in our PSM templates. (There are usually pre-existing S&H documents that can be modified to include the covered process rather than re-inventing the wheel.) What we DO provide are the “element guideline” and a template to get you started on your 1910.119(n) required “procedure for handling small releases” with the guidance that large releases are going to handled under the Emergency Action / Response Plan. We DO check that the EAP/ERP covers large releases in PHA’s and Compliance Audits and make appropriate recommendations when they address the issue. Is your PSM covered process integrated into your EPA/ERP?

Are Initial PHA and subsequent PHA (Revalidations) completed every five years?

The template program directs the client to do this and the PHA revalidation schedule (and other routine PSM tasks) is included in the MI-EL1 Mechanical Integrity Schedule. Are you providing this at the frequency required in the PSM system?

Are PHA, Incident Investigations and Compliance Audit recommendations properly addressed?

The templates provide compliant tools, a central location for all recommendations and an easy-to-use tracking sheet but it’s up to the client to address these items. Furthermore, the template Management System includes policy on how these recommendations are resolved. We have always made ourselves available for assistance and we’re fairly aggressive in closing out any contractor issues with the assistance of the Engineering / Service departments. Are you implementing the “Implementation Policy: Resolution of Recommendations” section which includes guidance on when it is appropriate to justifiably decline a recommendation? Have you provided adequate documentation to prove you have addressed the recommendations?

Has the employer fully implemented MOC procedures including updating PSI, operating procedures and training?

The templates provide streamlined MOC policies/procedures for Personnel, Documents/Procedures, Car-Seal and Equipment Changes. Are these procedures being implemented as necessary and are they being adequately documented to prove it?

Has employer defined the safe upper and lower operating limits?

We document this robustly in our templates and have recently made further improvements in the templates (Dec2016-Jan2017) which make it even simpler for updated programs. If you are using older versions of these templates, please consider updating the SOPs – perhaps as part of a regularly scheduled review program. If you break the work up, most facilities can make these changes fairly easily internally.

NH3 Specific PSM Questions

How were the ventilation calculations developed and what standards were used?

This should be provided by your installing contractor/engineering firm. The templates include an example of “compliant” documentation on this and we’ve seen that OSHA/EPA find it acceptable in the field. A common issue here is that an engineering document is provided that is not clear to non-engineers. Also common is that the document doesn’t provide the design basis RAGAGEP or states a RAGAGEP that is different than the one stated elsewhere in the program for design basis RAGAGEP.

When was your most recent ammonia charge? How do you verify ammonia purity?

If your contractor provided the NH3 they should be able to help answer this. The template PSM program includes a ROSOP QA (Quality Assurance) SOP that addresses this. You should demand and store a Certificate of Analysis during NH3 charging. As for ongoing purity tests, our MI program templates directs you to perform the NH3 purity test for water per IIAR Bulletin 110. Are you doing this at the frequency required in the RAGAGEP/PSM system? Are you documenting it adequately?

Show me a low side vessel data label that shows MDMT (This was answered using the U1A and MAWP and MDMT information). Verification of current operating conditions was also required.

Your installing contractor/engineering firm should provide this info but it’s up to you to run within the limits. Are you checking this during routine walkthroughs? Do your SOPs show acceptable ranges for operation and are these ranges inside the acceptable design window provided in the PSI?

Show me the process for draining oil from your system. How many oil pots are in the system? Is there a separate SOP for each oil pot, who drains the oil pots, have the operators been trained on the procedure and can you verify the equipment specific training?

Note that this is a “show me” type question so it’s imperative that the operators asked this question refer to the appropriate SOP. Template SOPs provide equipment specific oil drain SOP Procedural Sections. Can you document that your operators have received and understood this training? If contractors are providing the service, can they document that their technicians have received and understood the training? Are you (or your contractors) providing it at the frequency required in the RAGAGEP/PSM system? Are you documenting it adequately?

Is there external corrosion or ice build up on the refrigeration equipment? What is the frequency of removing ice on liquid pumps? What is the frequency of the PM? Is each asset maintained individually or as a group and when was the PM completed?

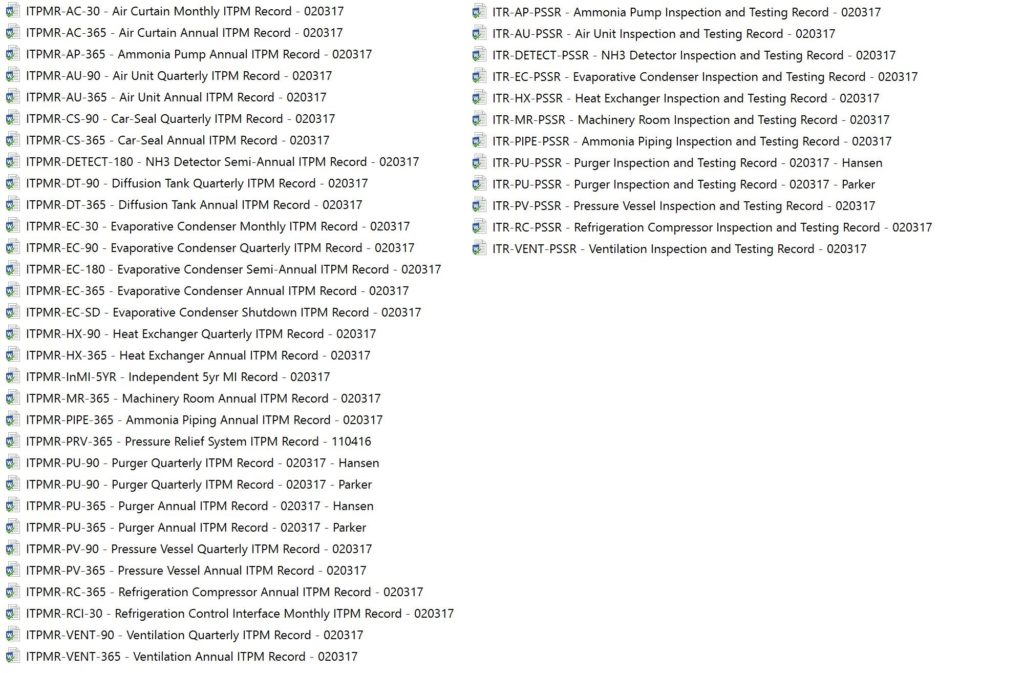

This is addressed in our MI program templates during walk-through’s as well as on each individual ITPMR which asks about excessive ice build-up. Are you implementing the walk-through and ITPMR at the frequency required in the RAGAGEP/PSM system? Are you documenting it adequately?

Are system logs used to document system conditions? The focus was on the continuous monitoring of the control system as well as the alarming and who receives the alarms.

If you use a modern control system (such as AEC) you likely have adequate logging. Walk-through documentation could help prove compliance. Are you implementing the walk-through at the frequency required in the RAGAGEP/PSM system Are you documenting the walk-through adequately? Hopefully you have addressed the alarm system in an SOP (either the System 101 ROSOP or the NH3/Vent ROSOP) so you have documented what happens to alarms. These questions should have been asked in the PHA.

With the exception of evaporators, condensers and associated piping is all equipment in a machinery room? What design codes and standards were used?

The first question directly out of IIAR 2-2014 which changed the rules a bit on equipment outside of a machinery room. It’s been roughly 3 years since that RAGAGEP came out and we are now seeing the question pop up RIGHT ON SCHEDULE. If you haven’t already compared your system to the 2014 IIAR 2, it would be appropriate to conduct a Gap Analysis (perhaps in conjunction with the PHA revalidation) to see where you stand. The template system documents the RAGAGEP itself clearly in a letter in the PSI.

Are machinery room doors and wall penetrations designed to be tight fitting with no gaps or openings. The focus was on door closers and gaskets around the perimeter of the doors. Verification that signage was on each door identifying restricted access was also required.

I’ve never seen this go as deep as door gaskets – frankly, we’ve always interpreted this far looser. Machinery rooms are designed to be negative-pressure areas (compared to other parts of the building) so this has not usually been a major concern. We certainly have seen it cited before where pipe penetrations through the machinery room wall were not sealed. Ask your technicians & safety people to look at this. Signage that meets IIAR 2 should have been evaluated as part of your PSSR, PHA and Compliance Audits.

Is access to the machinery room restricted to authorized personnel? How does the facility manage access, does the fire department have access, for the automatic door access where are these located, who has keys to the doors.

This is an issue you should have addressed in PHAs if you followed our PHA what-if checklist template. If you haven’t, there’s no reason not a do a quick mini-PHA on the issue.

How are the facility ammonia detectors tested and inspected? What is the frequency? Who inspected? What calibration procedures were used? Verification of the last two PM’s conducted.

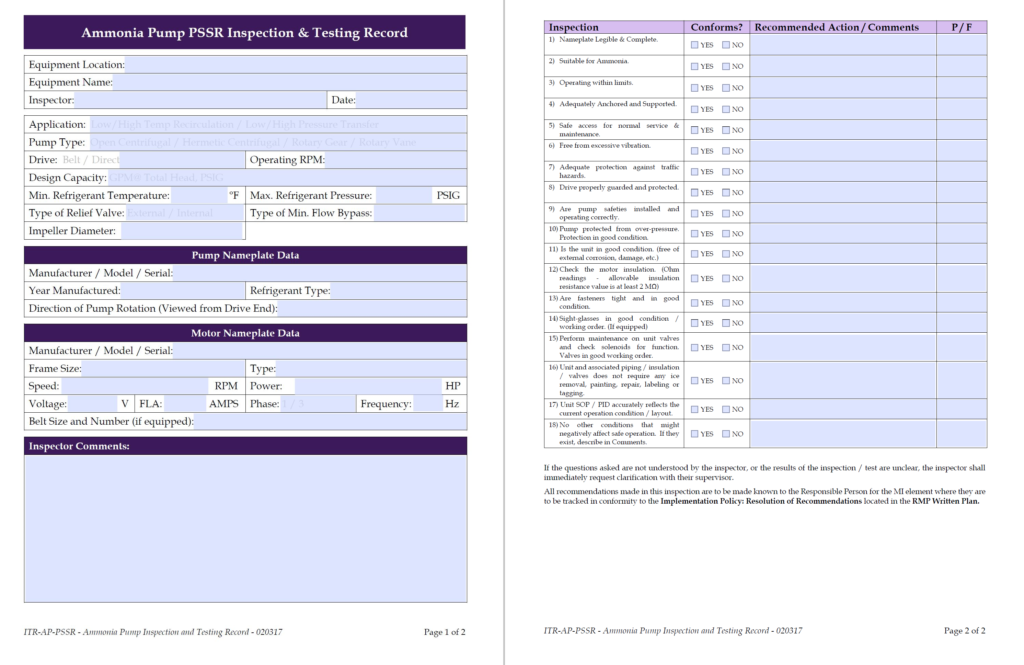

This was a significant point of contention for this inspection (in part) because they used an older version of the template which does not include recent revisions (over the past two years) to improve the MI performance of the template program. The current template includes: 1) Integrated MI procedures into the SOPs & 2) ITPMRs (Inspection, Testing & Preventative Maintenance Records) for standardized MI documentation. Are you implementing the ITPMRs at the frequency required in the RAGAGEP/PSM system? Are you documenting it adequately?