The October 17th, 2017 Ammonia release in Fernie, BC resulted in three fatalities:

On October 16, 2017, the curling brine chiller at the Fernie Memorial Arena was put back into operation after a seasonal shutdown. During the shutdown and seasonal maintenance, ammonia had been detected in the curling brine system, indicating that the curling brine chiller was leaking… A total of three people were found deceased in the mechanical room: the director of leisure services, the refrigeration operator, and a refrigeration contractor mechanic.

Three people died in a completely avoidable incident. If you want to know the particulars of the incident, I’d recommend you go read the Incident Report itself. While we can’t go back in time and avoid this particular incident, we can extract some valuable lessons from it to prevent a similar incident in the future.

There’s a lot that went wrong, but we’re going to focus on a few key failures in Mechanical Integrity, Process Safety, and Release / Incident Response. We’ll briefly discuss each failure and provide ten opportunities for improving your current Process Safety system.

Note: While this incident occurred in Canada, which does not have robust Process Safety regulation, we’re going to provide our analysis as if it was a PSM/RMP plant. Even if this incident had occurred in the US, the total system inventory was estimated at less than 1,000 pounds, placing it in the General Duty category. Most operators of these General Duty systems do not choose to implement a PSM system – hopefully this incident will cause them to re-evaluate that choice.

Equipment Age and installation: In 2011, the facility received a recommendation from their mechanical contractor to replace the chiller due to its age. It had been in service for about 24 years and had a life expectancy of 20-25yrs. (At the time of failure the chiller was in service for approximately 31yrs.) The facility actually budgeted for this replacement, deferred it, and then dropped the idea altogether. The report (and appendices) detail this decision making and indicates that the people making these decisions didn’t understand the underlying safety issues or the possible repercussions of these decisions. In part this was due to management turnover – the people who received the initial recommendation no longer worked at the facility when those recommendations were due to be implemented. Additionally, post-release, it was determined that the failed coupling was not properly supported.

Possible PSM citations: 1910.119(d)(3)(ii) for not installing the coupling per the manufacturers recommendations. 1910.119(d)(3)(ii) for equipment operating outside manufacturer’s recommended lifespan. 1910.119(e)(1) for the PHA not analyzing the hazards associated with operating outside the manufacturer’s recommended lifespan. 1910.119(j)(5) for operating the equipment with a known (service life) deficiency without assuring safe operation. 1910.119(m)(5) for not addressing and resolving a recommendation. (if the recommendation was made due to an indication of NH3 in the brine)

Opportunity #1: When a piece of equipment has a stated service life, you need to either replace the equipment per the recommendation or support your decision to keep it in service with a suitable engineering rationale.

Opportunity #2: When operators & contractors make recommendations, they need to provide CLEAR and defensible reasons for those recommendations.

Opportunity #3: When recommendations are delayed, deferred, or not completed, the operators & contractors need to ensure that the decision makers understand the implications of their decisions.

Opportunity #4: A Pre-Startup Safety Review (PSSR) and ongoing MI tasks need to ensure that equipment is installed correctly and maintained in a safe manner / arrangement.

Signs of Failure and Deficiency Response: The facility detected NH3 in the brine (by scent) in April of 2017 and then followed it up with a lab test of the brine showing over 3,000ppm of NH3 in June. The facility decided to continue operating the chiller and “monitor” it. A second test in August showed an NH3 concentration near 2,000ppm. Again, the facility decided to keep “monitoring” the situation. The report indicated that the personnel performing the tests and receiving the results didn’t understand the safety implications of them. Even after receiving the tests showing the chiller had failed, the facility decided to keep operating it. According to the report, there was no evidence the facility understood the hazards associated with a leaking chiller.

Furthermore, due to a miscommunication, the contractor believed the facility had taken the chiller out-of-service and they were preparing a bid to replace the leaking unit. The contractor’s recommendation to “monitor” the unit was likely meant to monitor it to see if the valves were leaking by, but the facility interpreted it as a go-ahead to continue operating the defective chiller until it could be replaced as long as they “monitored” it.

The contractor had no policy or procedure in place to deal with a failed chiller outside the usual troubleshooting, repair and replace activities. The investigators concluded that none of the people involved with the decision to continue operating the chiller had training or qualifications involving condition/risk assessment.

Possible PSM citations: 1910.119(j)(5) for operating the equipment with a known (integrity) deficiency without assuring safe operation. 1910.119(m)(5) for not addressing and resolving a recommendation. 1910.119(g)(1)(i) for not training personnel of the hazards associated with a leaking chiller.

Opportunity #5: Personnel reviewing test results need to understand the meaning of the test results and the safety implication of those test results.

Opportunity #6: When test results are provided to decision-makers, these results need to provide adequate information so that the decision-makers understand them and their safety implications.

Opportunity #7: When contractors are called to deal with deficient equipment, they will almost always provide guidance / estimates on how to repair / replace the equipment, but facilities should demand a risk assessment on continued operation of the equipment if they intend to continue its operation while planning and preparing for the repair / replacement.

From Appendix V of the report: “In the majority of instances, owner/operators relied heavily on the refrigeration contractor’s assessment of the equipment and evaluation of the NH3 indication in the brine samples. The owner is accountable for the safe condition and operation of the equipment but in some instances, deferment to the refrigeration contractor’s assessment and recommendations for the equipment was observed.”

Opportunity #8: When a facility outsources maintenance work, they often erroneously think that they are outsourcing the responsibility as well. It is important for a facility to understand that this remains their process and their responsibility. Ask tough questions of your contractors to ensure that you understand the condition of your system.

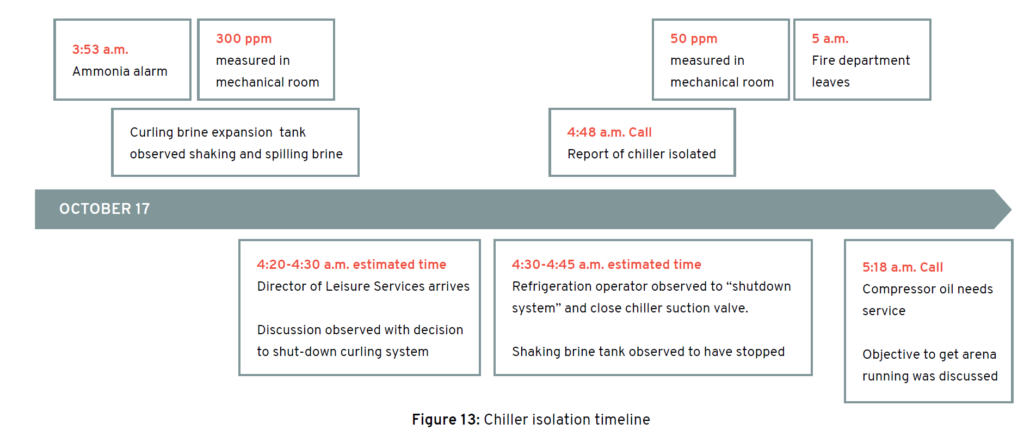

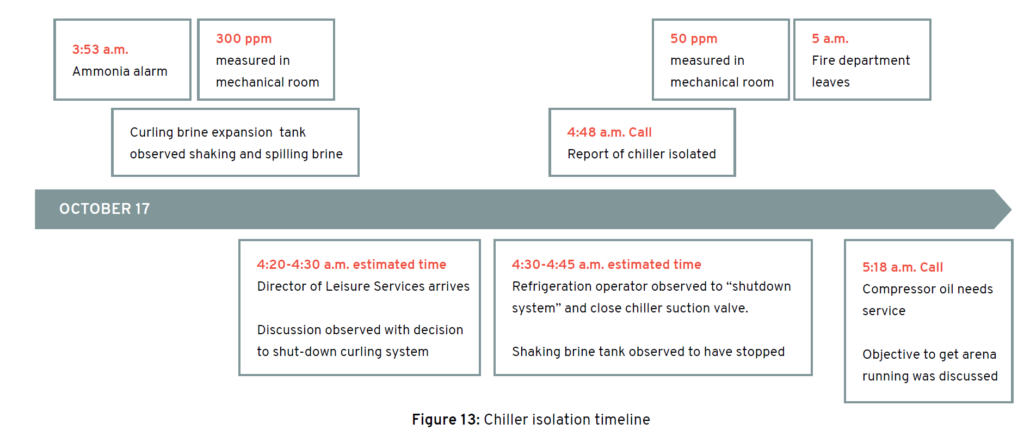

Facility and Contractor Incident Release Response: On the day of the release at 03:53 the machine room NH3 alarm registered 300ppm. Responding facility personnel observed the brine expansion tank shaking and spilling brine. At 04:30, the facility personnel shutdown the system and closed the chiller suction valve, observing that the shaking in the brine tank stopped. This should have indicated to the facility personnel that the separation between the brine and NH3 sides was completely compromised and that the brine loop was now full of ammonia. At 05:18 the facility personnel called the contractor to come in and re-configure the system to operate without the brine chiller.

At some point during the work, the personnel isolated the brine chiller, trapping the ammonia-laden brine in the chiller with no outlet available for it. As this ammonia-laden brine warmed up, the pressure inside the brine chiller rose and, at an estimated pressure of 30-150psig, a coupling on the brine-side of the brine chiller failed releasing the contents into the machine room and onto the personnel in the room. The estimated total NH3 release was 22 pounds (9lbs immediately vaporizing) resulting in an immediate concentration in the area of 20,000ppm which dissipated to about 5,000ppm over a period of 5 minutes.

The report uses electricity demand to conclude that the personnel did not attempt a pump-out of the brine chiller. Unlike a CSB report, the report does not go into the fatalities. We have no idea where the personnel were positioned in the room, or what – if any – PPE they were wearing at the time of the release. It can reasonably be surmised that they weren’t wearing any respiratory PPE at all.

Possible PSM citations: 1910.119(g)(1)(i) for not training personnel of the hazards associated with NH3 contaminated brine and the hazards of trapping it. 1910.119(h)(3)(ii) for the contractor not being trained in the hazards associated with NH3 contaminated brine and 1910.119(h)(2)(v) for the facility not ensuring this training occurred. 1910.119(n) for not providing “procedures to handle small releases.” 1910.119(f)(1)(i)(D) for not providing an emergency shutdown procedure. 1910.119(f)(1)(i)(E) for not providing an emergency operations procedure.

Opportunity #9: While we often train on the dangers associated with trapping NH3, the dangers of trapping NH3 contamination in a secondary loop is rarely discussed. Operator training in facilities that utilize secondary cooling loops must address contamination and its possible safety implications.

Opportunity #10: While it’s not possible to know for sure, it is extremely likely that all three of these fatalities could have been avoided if the personnel were wearing full-face APRs at the time of release. Note: They would have to have been wearing them, not have them “near-by.” APR’s aren’t magic.

090618 Update: Full WorkSafeBC Incident Report