Given the catastrophic nature of the hazards associated with PSM, the interrelationship of the PSM elements work together as a safety net to help ensure that if the employer is deficient in one PSM element, the other elements if complied with would assist in preventing or mitigating a catastrophic incident. Consequently, the PSM standard requires the use of a one hazard-several abatement approach to ensure that PSM-related hazards are adequately controlled. (OSHA, CPL 2-2.45A, 1994)

The text above, from OSHA’s old PQV (Program Quality Verification) audit is critical to understanding a key concept of successful Process Safety: The more ways you attempt to control a hazard, the more likely you are to be successful.

Sometimes this concept is referred to as the “Swiss Cheese Model.” I’ll quote from Wikipedia:

It likens human systems to multiple slices of swiss cheese, stacked side by side, in which the risk of a threat becoming a reality is mitigated by the differing layers and types of defenses which are “layered” behind each other. Therefore, in theory, lapses and weaknesses in one defense do not allow a risk to materialize, since other defenses also exist, to prevent a single point of failure. The model was originally formally propounded by Dante Orlandella and James T. Reason of the University of Manchester, and has since gained widespread acceptance. It is sometimes called the cumulative act effect.

To understand how this works in a functioning program, I want to point out how we recently addressed a single hazard in our program to show how many different ways we attempted to control it.

The hazard

In IIAR’s upcoming standard 6 “Standard for Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems” a hazard is identified and a prohibition is put in place to address that hazard:

5.6.3.4 Hot work such as the use of matches, lighters, sulfur sticks, torches, welding equipment, and similar portable devices shall be permitted except when charging is being performed and when oil or ammonia is being removed from the system.

The IIAR is recognizing that there is an increased likelihood of an Ammonia / Oil fire during charging operations and when oil / ammonia is being drained from the system. They are prohibiting Hot Work operations during these operations to remove potential ignition sources.

The Control(s)

You can make a (weak) case that simply referencing the RAGAGEP and inserting a single line in your Hot Work policy address the compliance requirement, but we’re going to need to do a lot more to make this prohibition a “real” thing in our actual operations.

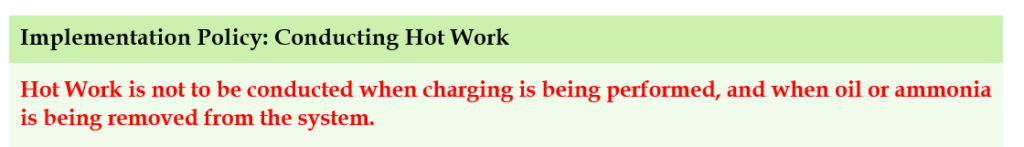

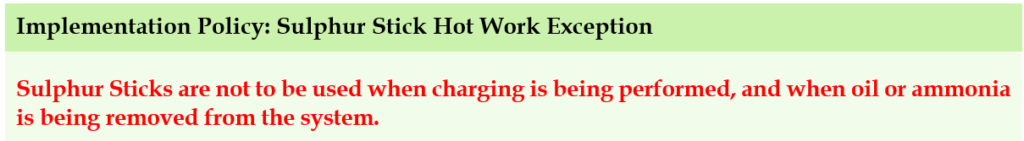

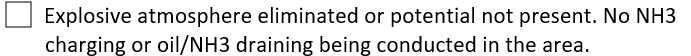

Control Group #1: The Hot Work element

In the element Written Plan, we added two new “call-out’s” in the two places they are likely to be seen when planning Hot Work policies. First, in the section on Conducting Hot Work:

Second, in the section on Sulphur Stick use:

Third, in the Hot Work Permit itself, we modified the existing question on flammable atmospheres:

Control Group #2: The Operating & MI Procedures

All procedures that involve oil draining, ammonia charging and ammonia purging already point to the LEO (Line & Equipment Opening a.k.a. Line Break) written procedure. This makes our job a bit easier here, since we only have to modify our LEO rather than the dozens of procedures that might include this type of work.

We modified the traditional LEO “General Precautions section to place a check for Hot Work during an existing requirement to canvas the area for personnel that may be affected by the LEO:

In the more advanced, two-step “Pre-Plan and Permit” version of our LEO, we modified the “Pre-Plan Template” to include a warning:

In both versions of the LEO permit itself, we added an explicit check:

![]()

Closing Thoughts

This one small RAGAGEP change points to a single hazard – a hazard that we’re now trying to control in six different ways. Notice that we’ve made all these changes so they are popping up throughout the program:

- In preparing policies for the associated work;

- In the course of preparing for the work itself;

- In the course of conducting the potentially hazardous operations.

This is critical because if we want to get the best “bang for our buck” in Process Safety, the safety portion has to be integrated into our actual processes on multiple levels.

Obviously, we’ll have to train on these changes to ensure that they’ll be effective. It’s quite possible that, after implementation, we’ll identify additional ways to prevent the hazard from being realized and will need to make further changes.